Building Adult Capacity and Expertise

Why Building Adult Capacity and Expertise Is Needed

The needed transformations in learning environments and experiences for students necessitates similar shifts in the ways educators are prepared and supported across the career pipeline. The science of learning and development has made clear that young people need educators who are well versed in the knowledge of how to support their academic, cognitive, social, and emotional development and the skills to create safe, affirming, and engaging learning environments. Educators cannot do this alone. They need a social commitment to building a system that supports their continuous learning and development. They also need comprehensive efforts to redesign schools to enable them to enact their knowledge and skills in a collaborative space where they and their students can thrive.

To build adult capacity to support the whole child, states can do the following:

-

1Design educator preparation systems that prepare teachers and school leaders with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to support whole child developmental needs and students’ development of 21st-century skills

-

2Adopt proactive teacher recruitment and retention strategies through high-retention pathways, including high-quality teacher residencies and rigorous Grow Your Own programs, service scholarships and loan forgiveness programs, strong hiring practices, and competitive compensation

-

3Support high-quality mentoring and induction programs that integrate whole child approaches and ensure that novice educators receive the comprehensive supports needed to remain in the profession and succeed

-

4Promote high-quality professional development linked to growth-oriented educator evaluation and improvement systems that support student and educator development and encourage teacher collaboration and reflection

-

5Support educator and staff well-being by adopting policies and practices that decrease stress and burnout and create positive working environments

Policy Strategy 1 Design Educator Preparation Systems for Whole Child Learning and Development

High-quality, comprehensive preparation of both school leaders and teachers is key to ensuring they have the knowledge and skills to support students’ whole child developmental needs. Evidence suggests that teachers who are better prepared feel more efficacious, experience less stress at work, and are more likely to stay in the profession. In contrast, teachers who lack comprehensive preparation are significantly more likely to exit the profession in their early years compared with those who are fully prepared. Similarly, high-quality principal preparation programs that prepare school leaders for the realities of supporting students and teachers and establishing a positive school climate can help disrupt the costly turnover of both principals and teachers.

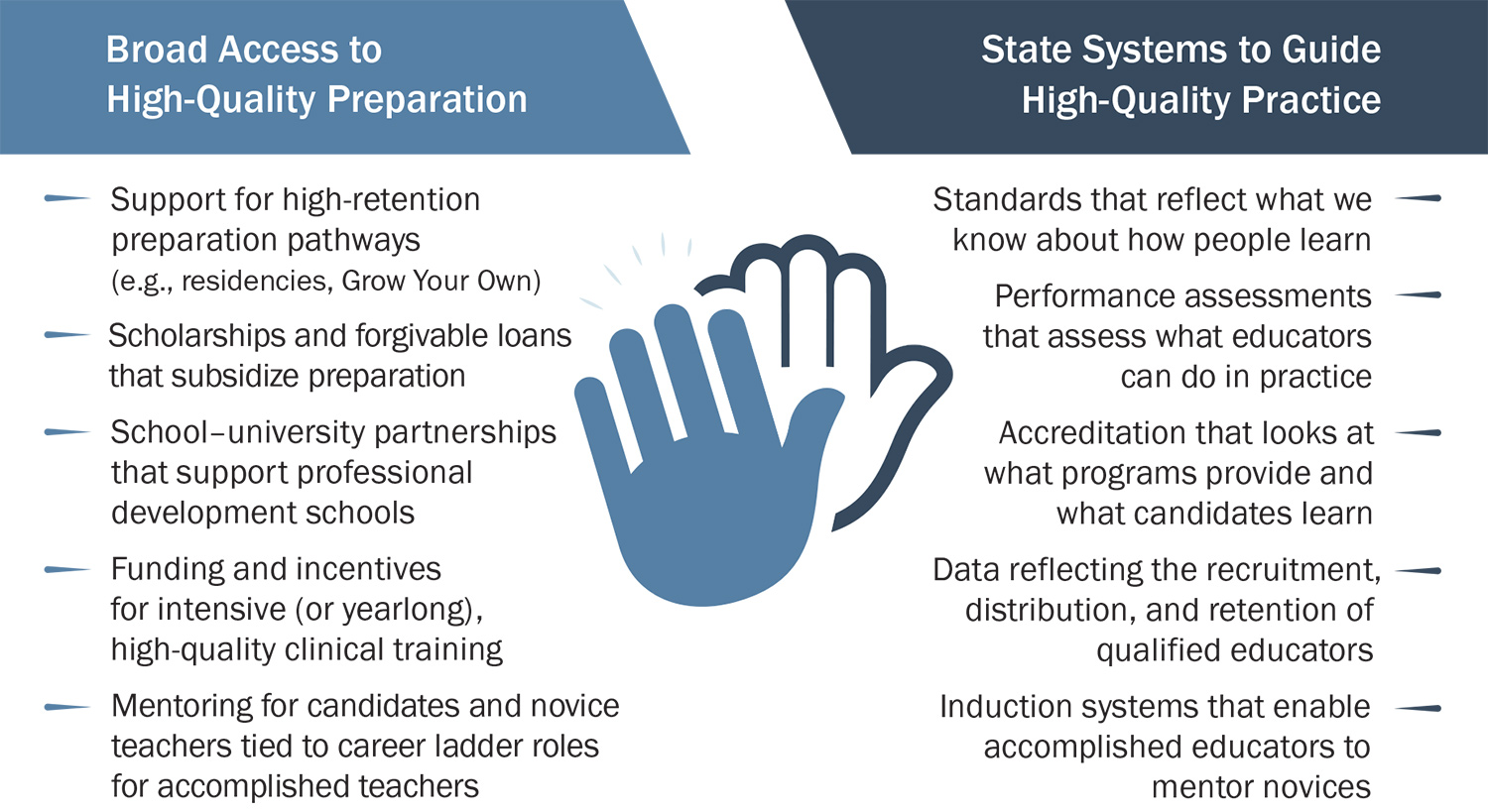

Strong certification and teacher preparation systems rely on the essential elements outlined in Figure 4.1. State systems function to guide high-quality practice, while strong certification and preparation systems support broad access to high-quality preparation and professional development. Taken together, these two areas of focus function as “two hands clapping”—working in ways that are necessarily interconnected. When both hands join together, the essential elements are in place for states to recruit a sufficiently large and diverse pool of aspiring teachers while also providing teacher candidates and new teachers the learning experiences that support their growth and development, plus assessments that allow them to demonstrate their ability to support learning for all students.

Source: Saunders, R. (2021). Preparing West Virginia’s teachers: Opportunities in teacher licensure and program approval. Learning Policy Institute.

To ensure a stronger educator pipeline, states need to ensure high-quality, evidence-based preparation systems for (1) k–12 teachers, (2) school leaders, and (3) early childhood educators.

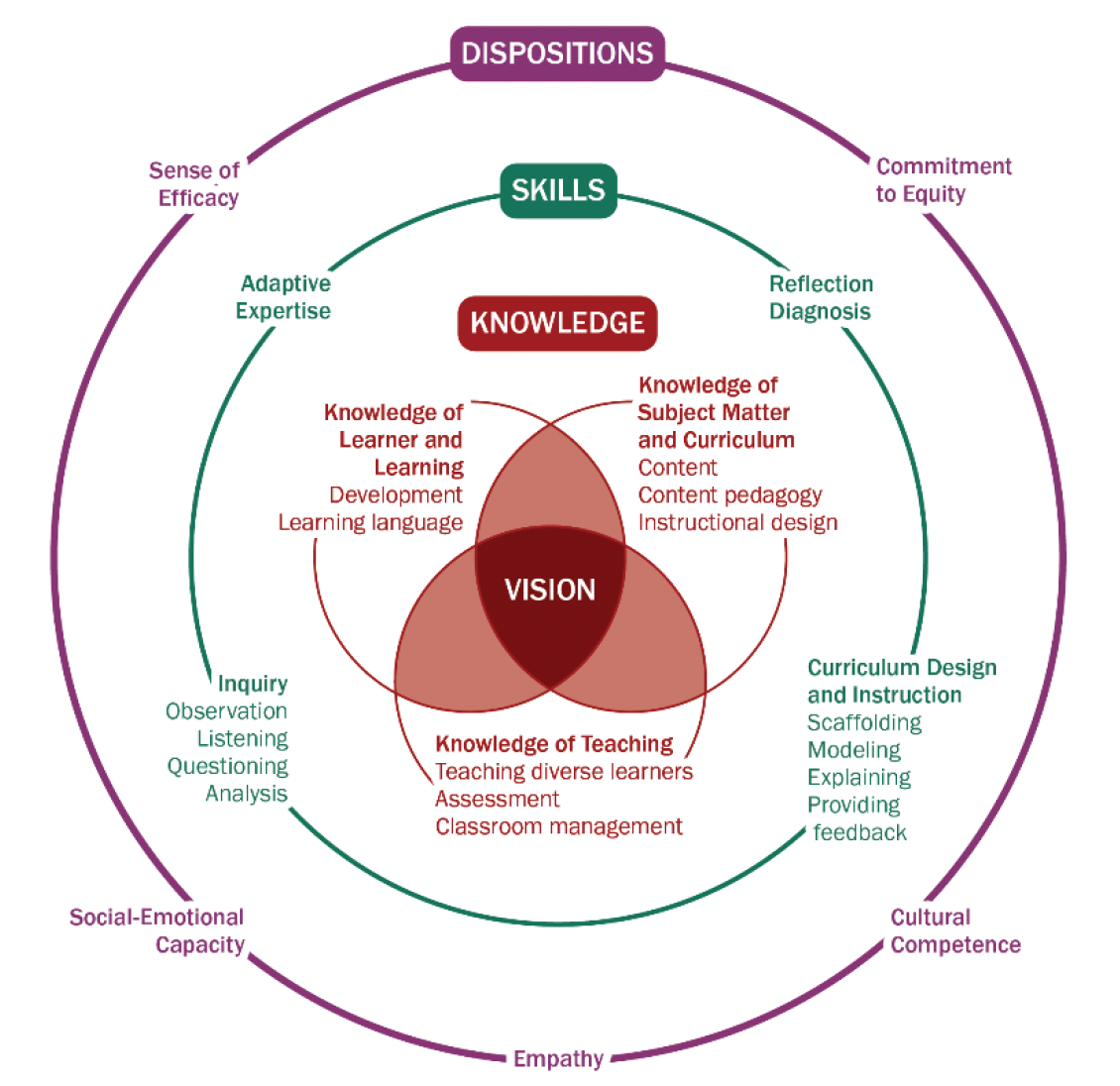

To support the kinds of shifts needed to foster whole child learning and development, policymakers need to ensure teacher preparation programs develop teacher candidates with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that support children and engage them and their families in culturally competent and equitable ways. The science of learning and development also demonstrates that teacher candidates need opportunities to develop important skills, including adaptive expertise to develop appropriate instruction for diverse learners; metacognition; inquiry skills; culturally sensitive listening and questioning skills; observation and analytic skills; curriculum design and instructional skills, such as the ability to scaffold lessons; and reflective and diagnostic skills. Teachers also need to be prepared with the beliefs, dispositions, and attitudes to support students’ learning and development. These include cultivating empathy and building trusting relationships, managing stress, developing cultural competence and affirming beliefs in all students’ abilities to succeed, and developing a sense of self-efficacy. (See Figure 4.2.)

Source: Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Schachner, A., & Wojcikiewicz, S. (with Cantor, P., & Osher, D.). (2021). Educator learning to enact the science of learning and development. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/859.776

|

Developing Culturally Responsive Educators Culturally responsive educators recognize the importance of infusing students’ experiences in all aspects of learning. Doing so enables educators to be responsive to learners—both by validating and reflecting the diverse backgrounds and experiences young people bring and by building upon their unique knowledge and schema to propel learning and critical thinking. To learn more about developing culturally responsive educators, please see Educator Learning to Enact the Science of Learning and Development. |

Stable principal leadership is key to attracting and retaining competent teachers, setting the direction of the school, and implementing and maintaining initiatives that foster learning and development. However, a recent national survey of principals found that many encountered obstacles to accessing high-quality principal preparation.

School leaders must be prepared with the same knowledge and skills as teachers in order to guide and support their work. They must also be able to integrate knowledge about how children learn and develop in order to inform school design and create a safe, collaborative, and productive learning environment for students, teachers, families, and caregivers. Research points to four key building blocks of effective school leadership programs:

-

Organizational partnerships that support learning through program partnerships with school districts and recruitment of strong candidates from the communities they serve

-

Programs structured to support learning through small cohorts and professional learning communities

-

Meaningful and authentic learning opportunities, including problem-based learning opportunities and field-based internships and expert coaching

-

Learning opportunities focused on what matters, including a focus on improving schoolwide instruction, attention to creating a collegial work environment, and use of data for improvement

Preparation programs for teachers and school leaders should be informed by well-defined standards that reflect the competencies, aptitudes, and skills needed to support whole child learning and development. Teacher and leader preparation programs should also include effective practices that are integrated with strong clinical experiences and performance-based assessments that assess how well educators meet these standards. Research has found that strong, research-aligned standards for teaching and school leadership are a key feature of high-achieving education systems, program quality, and student learning.

Teaching young children is complex, yet the bar to become an early childhood educator is often low. Early educator credentials also vary greatly by setting within states, from a high school degree in child care settings to a bachelor’s degree and teaching credential in preschool programs serving children of a similar age and need. While there is no one approach to early educator preparation, programs should equip early childhood educators with a deep understanding of child development and the complexities of educating young children. For example, features of promising models that prepare educators for credentials or degrees include:

-

Local educator pipelines and pathways

-

Relationship-building to promote persistence and success

-

Opportunities for extensive clinical practice in feedback-rich environments

-

Multifaceted supports that promote college persistence and success

-

Well-supported and diverse staff of instructors, advisors, and coaches

-

Community partnerships and funding to strengthen preparation

Video courtesy of The High Quality Early Learning Project.

Policy Actions

States can design systems to prepare educators who have the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to support students’ whole child learning and development by:

-

Developing strong educator licensure and certification systems. To build a strong educator licensure and certification system, states should establish standards that define high-quality practice to reflect what we know about how people learn and ensure that teacher and leader preparation programs incorporate needed knowledge and skills (e.g., knowledge of how to support the development of diverse learners in ways that incorporate the science of learning and development).

States can also develop or adopt standards-aligned performance-based assessments that assess what educators can do in practice. Teacher performance assessments typically require candidates to document their plans and teaching for a unit of instruction, film and analyze their teaching, and collect and evaluate evidence of student learning. States can also establish accreditation and program approval processes that look at what programs provide and what candidates learn in order to support continuous improvement and ensure programs are regularly preparing candidates to meet the standards. To support strong implementation, states can convene educator preparation programs to learn and share best practices and develop common understanding and alignment around what these practices look like and how to best support their development in teachers and leaders.

-

Adopting early childhood teacher credentials that focus on the specific needs of young children. Early educator credential requirements should adequately reflect the complexity of educating young children and ensure that preparation programs for early childhood educators equip educators with a deep understanding of child development and the complexities of educating young children. Credentials should also be aligned so that children with similar needs receive a teacher with a similar level of expertise.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of educator preparation systems.

Resources

- Educator Preparation Laboratory website

- Supporting Principals’ Learning: Key Features of Effective Programs (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

- To Reach the Students, Teach the Teachers: A National Scan of Teacher Preparation and Social & Emotional Learning (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, Report)

Policy Strategy 2 Adopt Proactive Teacher Recruitment and Retention Strategies

A large body of research suggests that certified and experienced teachers matter for student achievement and teaching quality. For example, a review of 30 studies found that teaching experience is positively associated with student achievement gains and that as teachers gain experience, students learn more and do better on other measures, such as school attendance. This research has also found that more experienced teachers not only increase student learning for the students they teach but have positive impacts across the school community as well.

A large body of research suggests that certified and experienced teachers matter for student achievement and teaching quality. For example, a review of 30 studies found that teaching experience is positively associated with student achievement gains and that as teachers gain experience, students learn more and do better on other measures, such as school attendance. This research has also found that more experienced teachers not only increase student learning for the students they teach but have positive impacts across the school community as well.

Yet despite existing research, data suggest that compared with prior decades, the teaching workforce has become less experienced. This is especially problematic given that inexperienced teachers (i.e., having less than 3 years of experience) tend to be concentrated in schools serving historically underserved students, particularly students of color. A recent report found that students enrolled in schools with a high proportion of students of color have less access to certified and experienced teachers compared with students in schools with a low proportion of students of color.

Several promising strategies have emerged to help recruit and retain well-prepared and diverse educators, including:

-

High-quality teacher residencies, Grow Your Own programs, and service scholarships and loan forgiveness programs, which are effective in addressing teacher shortages and encouraging historically underserved students to enter and remain in the profession

-

Hiring practices that promote educator quality and diversity

-

Competitive compensation for pre-k–12 educators

-

Principal preparation and development

|

The Teaching Profession Playbook The Partnership for the Future of Learning, in collaboration with 26 organizations and several individual experts, created the Building a Strong and Diverse Teaching Profession playbook, offering a comprehensive set of strategies that work together to recruit, prepare, develop, and retain high-quality teachers and bring greater racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity to the profession. The playbook includes examples of legislation; a curated list of publications, by topic, for further reading; a guide to talking about teacher shortages and strengthening the profession; and examples of research-based policies. |

Residencies offer a path to teacher certification through partnerships that ensure high-quality pedagogical training and clinical practice in yearlong programs and are typically targeted to postbaccalaureate candidates. Residents receive funding for tuition and living expenses while they apprentice with a master teacher in a high-need classroom for an entire school year and take related courses that earn them a credential and often a master’s degree. They repay this investment by committing to teach in a hard-to-staff position in the sponsoring district for at least 3 to 4 years after their residencies. Research suggests that residencies have the potential to increase the diversity of the workforce, improve retention of new teachers, aid in staffing of high-need districts and subject areas, and promote student learning gains. Eight key characteristics have been identified as important for high-quality residency programs:

-

Strong district–university partnerships

-

Coursework about teaching and learning tightly integrated with clinical practice

-

Full-year residency teaching alongside an expert mentor teacher

-

High-ability, diverse candidates recruited to meet specific district hiring needs, typically in fields where there are shortages

-

Financial support for residents in exchange for a 3- to 5-year teaching commitment

-

Cohorts of residents placed in “teaching schools” that model good practices with diverse learners and are designed to help novices learn to teach

-

Expert mentor teachers who co-teach with residents

-

Ongoing mentoring and support for graduates

Grow Your Own (GYO) programs are another way to address teacher shortages and recruit teachers of color into the workforce. These programs recruit local high school students, paraprofessionals, after-school program staff, or other local candidates from the community to enter a career in education and help them along their pathways into the profession. These models frequently underwrite the costs of teacher training and provide supports for candidates to succeed. As highlighted above, both residencies and GYO programs typically provide financial support to teacher candidates as a recruitment and retention tool. This is extremely important given that the cost of preparation is a common barrier to enter and remain in the teaching profession.

More than two thirds of individuals entering the education field borrow money to pay for their education, with the average debt ranging from $20,000 for those with a bachelor’s degree to $50,000 for those with a master’s. For college graduates of color, the debt weighs more heavily. Twelve years after graduating, Black graduates owe $43,000 more than white graduates, and though Latino/a college students tend to borrow similar amounts as white students, they are twice as likely to default on their student loans. With beginning teachers making 20% less than individuals with college degrees in other fields, the debt-to-income ratio is a major barrier for both recruiting well-prepared teachers and diversifying the teacher pipeline.

A 2016 national survey found that 1 in 4 public school teachers who left teaching and said they would consider returning identified loan forgiveness as extremely or very important in their decisions to return. Research points to teacher service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs as an effective strategy to recruit and retain high-quality educators. These programs help candidates pay for teacher preparation in exchange for a commitment to teach for several years, typically 3 to 5 years, and are often targeted to high-need fields and/or communities.

Hiring practices can also influence teachers’ decisions to enter, stay, or leave the profession. A review of the research on hiring practices found that hiring teachers late in the year negatively affects teacher recruitment, retention, and student achievement. The report also found that schools face barriers to using critical information. One such barrier is the limited time available to school staff for conducting observations of teacher practice, which in turn limits their ability to adequately assess the fit between a teacher candidate and the hiring school that could ensure better placement of candidates.

Another barrier to recruiting and retaining a diverse, high-quality educator workforce is low and inequitable compensation. Despite extensive research that highlights that compensation affects retention and recruitment, educators’ compensation continues to lag behind comparable professions. For example, a study found that in 30 states, mid-career teachers who head families of four or more are eligible for government subsidies, and many teachers work second jobs to supplement their salaries.

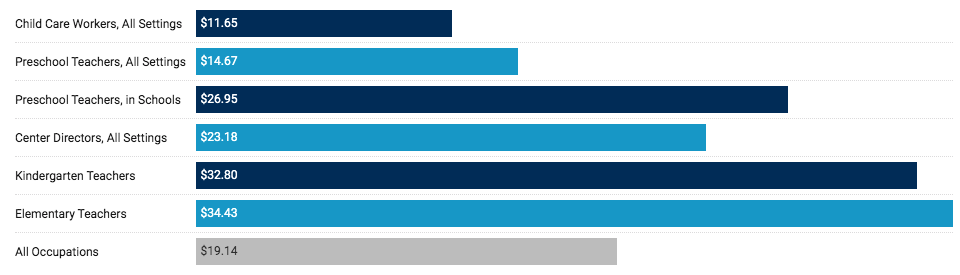

Similarly, early childhood education (ECE) programs struggle to recruit and retain qualified educators due to low wages and challenging working conditions. Child care and preschool educators, who are disproportionately women of color, earn one third to one half of the wages of k–12 educators, and over half rely on public assistance to make ends meet. (See Figure 4.3.) Federal and state ECE program regulations increasingly require educators to have higher levels of education, but compensation has lagged. This puts a high level of stress on educators, which is passed on to the children they teach and exacerbates turnover, affecting instructional quality. In addition, early childhood educators who work to increase their qualifications struggle to pay for college and have difficulty completing relevant coursework due to structural barriers.

Source: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. (2020). Early Childhood Education Workforce Index 2020: Early educator pay & economic insecurity across the states.

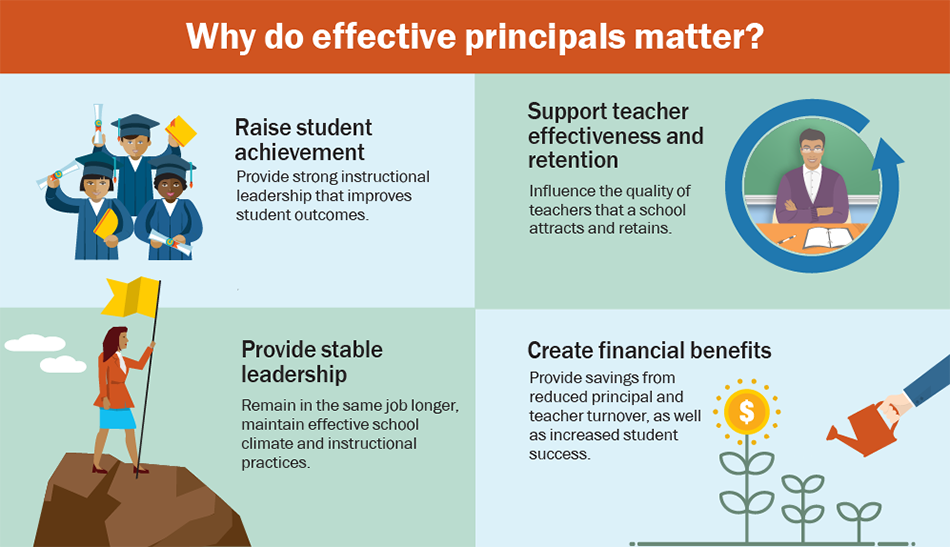

School leaders play a significant role in increasing teacher retention and supporting student achievement. Research has found that school leadership is second only to teaching among in-school factors that affect student learning, and a highly effective principal generates an additional 3-month increase in student math and reading learning. (See Figure 4.4.) Educators also frequently cite principal support as an influential factor in their decisions to remain in the school or profession. High-quality principal preparation programs can provide school leaders with adequate training to foster educator quality, lead and support instruction, create strong learning environments, and organize schools to support whole child development. Research has identified key features of effective programs, including organizational partnerships between preparation programs and districts, such as residencies and programs structured to support learning, and meaningful and authentic learning opportunities focused on what matters, such as networks of practice.

Source: Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Supporting principals’ learning: Key features of effective programs. Learning Policy Institute.

Policy Actions

States can adopt proactive strategies to address teacher shortages and recruit and retain diverse, well-prepared educators by:

-

Supporting high-retention pathways, such as high-quality teacher and leader residencies, that target shortage areas, particularly in high-need schools and communities. Research points to common features of a high-quality residency. Teacher residencies offer an accelerated path to teacher certification through district and university partnerships that ensure high-quality pedagogical training and clinical practice in yearlong programs. Residents receive funding for tuition and living expenses, plus a stipend or a salary, while they apprentice with a master teacher in a high-need classroom for an entire school year and take related courses that earn them a credential and often a master’s degree. They repay this investment by committing to teach in a hard-to-staff position in the sponsoring district for at least 3 to 4 years after their residency year while they receive additional mentoring.

-

Investing in and increasing access to service scholarships and loan forgiveness programs that support teacher candidates—particularly those from economically underserved families—in entering and remaining in the teaching profession. These programs typically subsidize the cost of teacher preparation in exchange for a commitment to teach for several years, typically in high-need content areas and specialties and/or in high-need schools (e.g., rural schools, schools serving high percentages of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch). To attract well-prepared teachers to the profession, service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs should do the following:

-

Cover all or a large percentage of tuition

-

Target high-need fields and/or schools

-

Recruit and select candidates who are academically strong, are committed to teaching, and are well prepared, with attention paid to recruiting candidates from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds

-

Commit recipients to teach for a minimum number of years (e.g., 4 years), with reasonable financial consequences if recipients do not fulfill the commitment (but not so punitive that they avoid the scholarship entirely)

-

Be bureaucratically manageable for participating teachers, districts, and higher education institutions

-

Creating or expanding high-quality Grow Your Own (GYO) programs to help recruit and prepare community members to teach in local school districts. Beyond allocating funding to help seed these programs, states can ensure access to high-retention GYO programs by requiring that programs do the following:

-

Design structured pathways for candidates to advance toward required teaching credentials and certification at various stages of their careers

-

Provide paid work-based experience under the guidance of a trained mentor teacher that aligns with educator preparation coursework

-

Incorporate coursework and learning experiences that build knowledge of curriculum development and assessment; learning and child development; students’ social, emotional, and academic development; culturally responsive practices; and collaboration with families and colleagues

-

Recruit linguistically and culturally diverse candidates who are both reflective of and responsive to the needs of the local community

-

Provide wraparound supports for candidates through the recruitment, preparation, and induction years (e.g., cohort structure, scholarships, licensure test preparation, assistance navigating college admissions process)

-

Support strong collaboration and coordination across school districts, educator preparation providers, and community organizations

In addition, states could increase the number of high school pathway programs for teaching, such as teacher cadet and/or dual enrollment opportunities for future teachers.

-

Implementing proactive preparation and hiring practices that promote educator quality and diversity. For example, states can foster district partnerships with local teacher preparation programs—including at minority-serving institutions, historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, tribal colleges and universities, and Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–serving institutions. Such partnerships can leverage service scholarships or other financial incentives to help make the programs more attractive and accessible. Preparation programs can work with local school districts to coordinate student teaching placements, and state policies can support districts in shifting hiring timelines to earlier in the school year to provide school leaders access to high-quality candidates, including educators of diverse backgrounds.

-

Promoting educator quality and diversity by reducing barriers in licensure or certification systems. States can examine barriers in current licensure and certification systems, including assessment requirements, that can constrict the teacher pipeline or disproportionately impact potential teachers of color and that are often poor predictors of later teaching effectiveness. For example, states can allow candidates multiple pathways to demonstrate subject matter and basic skills competence, such as through college courses and majors, rather than solely through traditional standardized exams. States can also consider high-quality teacher performance assessments, which measure what candidates do in the classroom, require candidates to demonstrate their abilities to support learning, and have been found to predict teaching effectiveness.

-

Providing competitive compensation across the state by continuing to increase teacher salaries to be more comparable to those of other college-educated professionals and closing within-state teacher salary gaps across districts. More competitive compensation can be a critical strategy to recruit and retain effective educators at all levels, although different approaches may be necessary depending on the state, regional, and district contexts. For example, states could work to close wage gaps between districts by providing competitive compensation through a variety of strategies, including examining their current school funding formulas and providing stipends and other forms of compensation targeted to teachers in high-need subjects and schools (e.g., loan forgiveness, which effectively acts as a compensation boost; stipends for National Board Certification; or bonuses).

-

Raising early educator compensation and adopting other effective strategies to recruit and retain early childhood educators. K–12 teachers earn two to three times as much as early educators. To address this large wage gap, states can offer competitive compensation to early childhood educators, on par with that of k–12 teachers. States may also provide financial and academic support, such as supporting early educators to pay for degree and credential attainment or adding a stipend for National Board Certification. States can improve retention of early educators by improving their working conditions, such as by ensuring access to paid planning time and in-service professional development on par with what k–12 educators receive.

-

Supporting high-quality principal preparation and development. States can invest in high-quality principal preparation and professional development programs that train school leaders in creating productive, professional, and collaborative school working environments. For example, districts can offer service scholarships for aspiring principals to participate in high-quality preparation programs; provide staff support to free up principals’ time to participate in professional development activities; offer trainings at times and locations that are more convenient; and work professional learning into district feedback, evaluation, and mentoring systems. Districts can leverage federal funds under ESSA Title II, Part A to help principals access timely and relevant preparation and development opportunities.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of proactive teacher recruitment and retention strategies.

Resources

- Building a Diverse Teacher Workforce (Education Commission of the States, Brief)

- Strategies in Pursuit of Pre-K Teacher Compensation Parity: Lessons From Seven States and Cities (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment; National Institute for Early Education Research, Report)

- Taking the Long View: State Efforts to Solve Teacher Shortages by Strengthening the Profession (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

Policy Strategy 3 Support High-Quality Mentoring and Induction Programs

High-quality mentoring and induction programs for novice teachers are another effective strategy to improve educator retention, support professional growth, and increase student outcomes. Research has identified key elements of high-quality induction programs that are associated with lower levels of turnover among novice teachers. For example, effective induction programs include mentoring, coaching, and feedback from experienced teachers in the same subject area or grade level; opportunities to observe expert teachers; orientation sessions, retreats, and seminars; and having regularly scheduled collaboration time with other teachers. Research has also found that educators who receive these types of induction supports are more than twice as likely to remain in the profession compared with educators who lack these supports. Induction programs have also been linked to improved instructional effectiveness and positive impacts on student achievement in the years following the program.

High-quality mentoring and induction programs for novice teachers are another effective strategy to improve educator retention, support professional growth, and increase student outcomes. Research has identified key elements of high-quality induction programs that are associated with lower levels of turnover among novice teachers. For example, effective induction programs include mentoring, coaching, and feedback from experienced teachers in the same subject area or grade level; opportunities to observe expert teachers; orientation sessions, retreats, and seminars; and having regularly scheduled collaboration time with other teachers. Research has also found that educators who receive these types of induction supports are more than twice as likely to remain in the profession compared with educators who lack these supports. Induction programs have also been linked to improved instructional effectiveness and positive impacts on student achievement in the years following the program.

While many novice educators have access to some type of mentoring or induction programs, survey data suggest that many do not receive the comprehensive supports that research has found to be effective. The quality of such programs also varies widely, and the programs are less likely to be available for educators in low-income schools. During the Great Recession, the number of states supporting mentoring and induction programs decreased, and fewer teachers received mentoring in 2012 than in 2008. A 2019 state policy scan found that 31 states require induction and/or mentoring support for new teachers, and roughly half of those states require those programs to last 2 or more years. Given the benefits of mentoring and induction programs, state efforts should be directed at increasing access to these programs and ensuring their alignment with the evidence-based elements of effective programs. States can also increase the number of National Board Certified Teachers (NBCTs) serving as mentors. National Board Certification allows applicants to demonstrate teaching expertise through a rigorous, standards-based performance assessment requiring submission of a teaching portfolio, videos of teaching, reflections on teaching, lesson plans, and evidence of student learning. Research has found that students taught by novice teachers mentored by NBCTs had a higher level of achievement than the students of novice teachers mentored by non-NBCTs.

Policy Actions

States can support high-quality mentoring and induction programs by:

-

Increasing access to comprehensive teacher mentoring and induction programs for all new teachers. Comprehensive mentoring and induction programs are an important part of ensuring that novice pre-k–12 teachers receive the types of supports that keep them in the profession and that build their capacities to meet the needs of all students. States may consider increasing funding to provide more comprehensive teacher mentorship and induction programs for teachers in their first and second years of teaching and more intensive supports for those serving under emergency certification. Because novice teachers tend to be disproportionately concentrated in districts serving high proportions of students from low-income families, states should consider distributing funding for mentoring and induction programs based on the number of novice teachers teaching in a district. Such funding may be coupled with training to support mentors’ work with new teachers. States should also continue to study the effectiveness of their mentoring programs and refine their designs as needed.

-

Developing new or supporting existing mentoring and induction models that highlight and integrate whole child approaches and mentor–teacher training and coaching. For example, states can build the capacity of educator and mentor cadres with expertise in whole child approaches to improve the quality of the learning environment (e.g., trauma-informed instruction, restorative practices, integration of social and emotional learning, project-based learning, and culturally responsive teaching). States can also increase investments in National Board Certified Teachers, who can serve as skilled mentors for novice teachers as well as residents and student teachers, and who can bring their expertise to other critical teacher leader roles.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of mentoring and induction programs.

Resources

- High Quality Mentoring and Instructional Coaching Practices (New Teacher Center, Guide)

- Mentoring & Induction Toolkit 2.0: Supporting Teachers in High-Need Contexts (American Institutes for Research, Toolkit)

- State Mentoring Policies Key to Supporting Novice Teachers (National Association of State Boards of Education, Brief)

Policy Strategy 4 Promote High-Quality Professional Development Linked to Growth-Oriented Evaluation Systems

As with children’s learning and development, educators also require a supportive context and collaborative culture in order to improve and grow their whole child teaching practice. Creating this environment requires a focus on individual practitioner development as well as a commitment to a broader systems-level approach to supporting educators at the school and district levels. Professional learning systems should therefore be guided by helping educators continue to develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to create the learning environments and rich learning experiences students need to thrive, as well as by a vision for collective school and system redesign that allows teachers and leaders to implement these changes.

To create a system in which educators feel supported to learn and grow throughout their careers, states need to (1) support districts in providing high-quality professional development (PD) and (2) develop growth-oriented educator evaluation and improvement systems.

Research suggests that well-designed and implemented PD can strengthen k–12 teachers’ instructional practices and improve student outcomes. A 2017 review of 35 studies that demonstrated a positive link between teacher PD, instructional practices, and student outcomes identified seven characteristics of effective PD:

-

Focuses on the curriculum content that teachers teach and strengthens teaching strategies associated with specific curriculum content

-

Engages teachers in deeply embedded, contextualized opportunities that provide hands-on opportunities for teachers to design and try out new strategies

-

Supports teacher collaboration that is sustained over a period of time and offers valuable opportunities for educators to learn from each other, discuss best practices on how to support student needs, and grapple with issues related to instructional practices and materials

-

Provides teachers with clear models of effective practices, including lesson and unit plans, sample student work, observations of peer teachers, and video or written cases of accomplished teaching

-

Provides coaching and expert support that guides learning in the context of teachers’ individual practice and needs

-

Provides built-in time for teachers to receive feedback on their practice and to engage in opportunities for self-reflection

-

Provides adequate time to learn, practice, implement, and reflect on new strategies by engaging teachers over weeks, months, or even academic years, rather than in short one-off workshops

Like k–12 teachers, most early educators lack access to coaching and high-quality PD, both of which have been found to improve instructional quality. Coaching—direct observation paired with individualized feedback from a mentor—has been linked to improved teacher–student interactions, less teacher burnout, and increased teacher retention. Coaching is currently an allowable use of funds in the Child Care and Development Block Grant and is a particularly high-leverage strategy for quality improvement.

The need for teachers to receive more personalized, relevant, and easily accessible PD has led more states to develop or adopt micro-credentials for teachers and administrators. Micro-credentials—self-directed, job-embedded, competency-based, and research-based professional learning opportunities that “verify a discrete skill that educators demonstrate by submitting evidence of application in practice”—hold promise for providing learning opportunities in addition to traditional PD, but the approach is still new, and little research has been done to measure its effectiveness. Early survey data of teachers using micro-credentials found that teachers liked the approach and felt they were able to use what they learned in their teaching practice. However, as states consider expanding the use of micro-credentials as part of their broader professional learning and advancement system, they should consider their intended purpose and ensure alignment with high-quality standards for professional learning. Additionally, micro-credentials, like all high-quality PD, work best when paired with collaboration, opportunities to learn and practice new skills, and time to reflect on what has been learned.

To create an evaluation system that develops well-prepared, effective educators, professional teaching standards must be linked to student learning standards, curriculum, and assessment to ensure a seamless relationship between what teachers do in the classroom and how they are assessed. A systemic approach to educator evaluation should move away from reliance on single standardized test scores and value-added measures that have been found to be unreliable and biased. Instead, the approach should be based on a collection of multifaceted evidence of teachers’ contributions to student learning and the broader school culture. Evidence of student learning can include teacher observations, portfolios of student work, student performance on curriculum-aligned tests (federal, state, district, school, or educator created), and measures of student progress toward set learning goals.

Well-rounded evaluations may also consider measures of a teacher’s ability to meet the needs of the whole child, including creating authentic and meaningful instruction and assessments; using student data to improve instruction; establishing a safe, inclusive, and culturally responsive classroom environment; engaging with families and caregivers; and contributing to a professional culture through consistent reflection and collaboration with other teachers. Examples of measures to evaluate these objectives may include peer observations, self-assessments, student and family surveys, and evidence of professional and leadership responsibilities within the school.

An evaluation system focused on growth and improvement should consider measures of student learning and contributions to school culture and provide opportunities for continuous goal setting, formal professional development, and job-embedded learning opportunities. It should also create structures that support high-quality evaluations, including time and training for evaluators, the support of master or mentor teachers to provide expertise and coaching, and high-quality learning opportunities to support teacher growth.

Policy Actions

States can promote high-quality professional development and growth-oriented evaluation systems by:

-

Creating and supporting effective PD experiences that help educators meet whole child needs through state departments of education, regional collaboratives, networks of school districts, and other providers. For example, states can provide, or work with districts to provide, PD for all educators on supporting students’ social, emotional, academic, and cognitive growth and development; developing and using authentic assessments; creating identity-safe classrooms and culturally responsive curricula and instruction; building strong family–school relationships, including through providing ongoing, flexible, and linguistically responsive communication and engagement opportunities; implementing evidence-based personalized learning structures and experiences; and using educative and restorative practices that are trauma informed and healing focused. These trainings can be coordinated with other youth-serving community partners to support consistency of practice and leverage resources and expertise across settings.

In addition, states can support the development of high-quality micro-credentials as part of a larger professional learning system. Early research shows that states can do this by establishing quality standards to ensure micro-credentials hold consistent value to educators regardless of where they teach. To ensure that micro-credentials positively impact educator learning and professional growth, states can establish a well-designed system for developing, implementing, and evaluating micro-credentials; provide support and resources to educators while they work on a micro-credential (e.g., individualized coaching, timely feedback, opportunities to collaboratively learn with peers); and ensure educator access to micro-credential data to understand their impact on teaching practice and student learning.

-

Supporting schools and districts in adjusting and reconfiguring school schedules to allow for new staffing structures, such as team teaching, and providing increased opportunities for teachers to participate in ongoing teacher collaboration. For example, states can encourage schools and districts to provide sufficient and common planning time to discuss and develop strategies to meet the whole child needs of their students and ensure that both early childhood and k–12 educators are provided ongoing high-quality PD to develop and improve their teaching skills and practices. States can also support, through guidance and incentives, the formation of professional learning communities, interdisciplinary teaching teams, or co-teaching partnerships to foster peer-to-peer relationships and information sharing between staff.

-

Investing in and supporting access to coaching and other job-embedded supports for all early childhood education providers. For example, states can leverage federal funds from the Child Care Development Block Grant to support high-quality coaching in all ECE classrooms. Funding could go to programs that meet research-based program design standards, including coaching frequency and coaching qualifications.

-

Developing and adopting teacher and administrator evaluation systems that recognize the full range of student development and learning and are based on multiple forms of evidence of student learning. Evaluations should be based on authentic measures of teacher and administrator performance and growth, which can include formal and informal observations and feedback conducted by trained observers using evidence-based protocols, peer-to-peer observations, student and family surveys, evidence of teacher collaboration, and mentorship and leadership experiences. This information can be used to develop PD plans that allow teachers and administrators to set goals and measure progress toward meeting them and that provide administrators insight into schoolwide PD and peer mentoring opportunities.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of PD and school structures that support educators.

Resources

- Empowered Educators: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teaching Quality Around the World (National Center on Education and the Economy, Brief)

- Principles for Teacher Support and Evaluation Systems (Council of Chief State School Officers, Guide)

- Teaching the Whole Child: Instructional Practices That Support Social-Emotional Learning in Three Teacher Evaluation Frameworks (American Institutes for Research, Brief)

Policy Strategy 5 Support Educator and Staff Well-Being

To create and maintain learning environments that enable all youth and adults to thrive, it is necessary to support the social, emotional, and mental health and well-being of educators and school staff. A national survey found that 46% of educators report high daily stress during the school year, tied with nurses for the highest rate among all occupational groups. Educators who have greater stress and show more depressive symptoms create classrooms that are less conducive to learning, which in turn affects students’ academic performance. When teachers are highly stressed, students show lower levels of social adjustment and academic performance, whereas when teachers are more engaged, students show higher levels of engagement and achievement. Teacher stress has only been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the 2020–21 school year, teachers were more likely to report a high level of job-related stress and symptoms of depression than the general adult population, and more teachers are now reporting they are likely to leave the profession than before the pandemic.

To create and maintain learning environments that enable all youth and adults to thrive, it is necessary to support the social, emotional, and mental health and well-being of educators and school staff. A national survey found that 46% of educators report high daily stress during the school year, tied with nurses for the highest rate among all occupational groups. Educators who have greater stress and show more depressive symptoms create classrooms that are less conducive to learning, which in turn affects students’ academic performance. When teachers are highly stressed, students show lower levels of social adjustment and academic performance, whereas when teachers are more engaged, students show higher levels of engagement and achievement. Teacher stress has only been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the 2020–21 school year, teachers were more likely to report a high level of job-related stress and symptoms of depression than the general adult population, and more teachers are now reporting they are likely to leave the profession than before the pandemic.

Given that stress impacts educator performance and student outcomes, it is important to provide supports for educators to manage their stress and well-being. Research has found that educator well-being can be enhanced by:

-

A supportive administration, particularly in creating a collegial, supportive school environment, which can reduce teacher stress and increase teacher engagement

-

Mentoring and induction programs, which can improve satisfaction and retention as well as student academic achievement (See Policy Strategy 3: Support High-Quality Mentoring and Induction Programs for more information.)

-

Workplace wellness programs, which can result in reduced health risk, health care costs, and staff absenteeism

-

SEL programs, which can improve behavior and promote social-emotional skills among students, helping to reduce teacher stress and creating more positive engagement with students

-

Mindfulness and stress management programs, which can help educators develop coping and awareness skills to reduce anxiety and depression, and improve health

Policy Actions

States can support educator and staff social, emotional, and mental health and well-being by:

-

Gathering data from educators on school environments and working conditions as well as their general health and wellness. The state may gather data by conducting staff surveys, through instruments such as the TELL survey (used by multiple states, including Kentucky, Ohio, and Oregon), and tracking educator chronic absenteeism. Such data can help support decisions about allocating resources to improve working conditions. In addition, the surveys can also give educators and staff an opportunity to express their perceptions of the school environment and identify supports to help improve working conditions, manage stress, and promote wellness.

-

Adopting policies and providing guidance for districts and schools on creating healthy school environments and implementing a comprehensive wellness approach to support educators and staff in adopting healthy lifestyles and managing stress. Policies and guidance may include:

-

Workplace wellness programs that improve teacher health, attendance, and engagement

-

Social-emotional supports that help teachers improve engagement with students, families and caregivers, and their colleagues

-

Teacher stress management programs that improve teacher performance and complement health approaches, such as mindfulness meditation

-

School redesign that creates the conditions for the transmission and sharing of knowledge among teachers

-

Comprehensive educator wellness initiatives integrated into existing programs across the career continuum, including preservice, mentoring and induction, professional learning, and leadership training and development

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of supporting educator and staff well-being.

Resources

- A Comprehensive Guide to Adult SEL (Panorama, Guide)

- Supporting Educators Through Employee Wellness Initiatives (National Association of State Boards of Education, Brief)

- Teacher Stress and Health (Pennsylvania State University, Brief)