Investing Resources Efficiently and Equitably

Why Resources Need to Be Invested

Equitably and Efficiently

Funding for k–12 education comes from several sources, including federal (7.8%), state (46.9%), and local sources (45.3%). When used well, these resources can close opportunity and achievement gaps. Nevertheless, many state school finance systems have been deemed inadequate. The Great Recession led to a significant loss of state and local tax revenue that supports public schools, but even after the economy rebounded, all but four states failed to restore funding to pre-recession levels. Inadequate school funding disproportionately affects students of color and those living in poverty. As a result, students who are most affected by structural inequities—including housing and food insecurity, lack of health care, and inadequate community services—may also face the double impact of being enrolled in under-resourced schools.

Early childhood education, k–12 education, and other youth-serving systems are also burdened by funding and resource streams that operate in an incoherent and often conflicting manner. Funding to support young people comes from a broad array of federal and state agencies and programs with little to no coordination to ensure funds are spent to have the greatest positive impact on children and youth. This siloed approach to funding and spending without a clearly articulated vision has led to inefficiencies and fragmentation that stands in the way of meeting young people’s full learning and developmental needs. States should pursue strategies to create adequate and equitable funding formulas and use resources in a coherent and efficient manner.

To accomplish this, states can do the following:

-

1Adopt adequate and equitable school funding formulas that prioritize high-need schools and support all young people in having access to the whole child opportunities they need to succeed

-

2Allocate adequate funding across the developmental continuum to ensure children and families are supported from birth to age 5

-

3Blend and braid federal, state, and local resources to reduce fragmentation and improve alignment across funding streams and programs

-

4Leverage and align federal funds in ways that support all young people in having access to the whole child opportunities they need to succeed

-

5Invest in community schools and integrated student supports to better serve the holistic needs of children and families

-

6Close the digital divide to ensure every child has access to appropriate technology and connectivity to meet their whole child needs

Policy Strategy 1 Adopt Adequate and Equitable School Funding Formulas

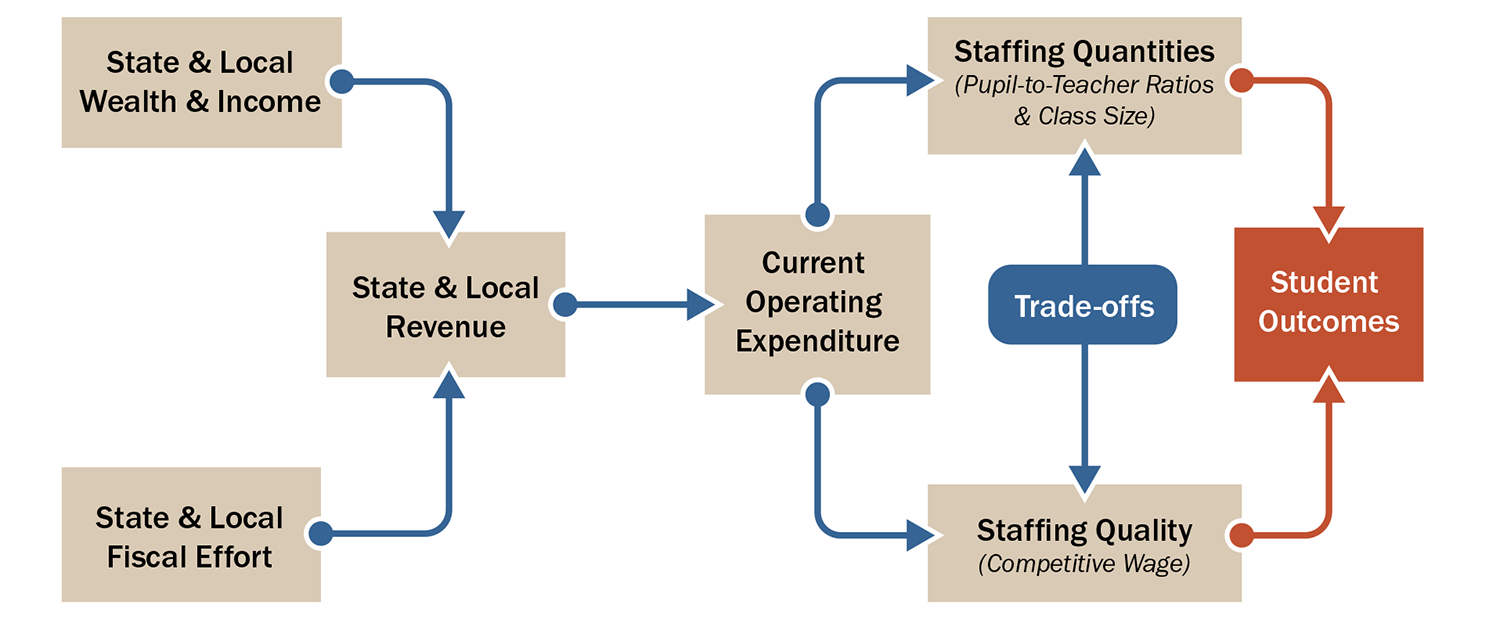

Public schools in the United States are among the most inequitably funded of any in the industrialized world. This is exacerbated by unequal local property tax bases and by states not investing enough funding to address these disparities. Despite evidence that money matters for student success in school and life, many state school funding systems do not provide adequate and equitable school funding, particularly for low-income schools. (See Figure 5.1.) Several states have moved in the direction of aligning school funding formulas with the resources needed for students to meet the state’s goals for education, or adequacy-based funding.

Source: Baker, B. D. (2017). How money matters for schools. Learning Policy Institute.

Given the great inequities in the United States, including the highest rates of child poverty in the industrialized world, schools should be providing more intensive services for children in high-poverty areas than in more affluent areas. However, the opposite is true. In many states, districts serving affluent students receive as much or more money than those serving children in poverty.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, an analysis of funding equity across the United States found that school districts serving predominantly students of color receive $1,800, or 13%, less per student of combined local and state funding than those serving predominantly white students. Furthermore, poverty in the U.S. does not impact all children equally. Children of color are 2.5 times more likely to be poor than their white peers, and Black children are more likely than white children to live in states where Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds are the lowest.

Students who live in poverty, are homeless or in foster care, are English learners, or are identified for special education have additional needs and often require additional educational resources to achieve the standards and goals set by the state. This should be recognized in school funding formulas with greater per-pupil spending weights. Districts with concentrations of such pupils carry more responsibility to provide student support services and intensive teaching and learning opportunities, which need to be recognized in school funding systems as well.

Policy Actions

States can adopt an adequate and equitable school funding formula by:

- Prioritizing the needs of historically underserved children and adolescents. For example. For example, states can calculate district funding beginning from a uniform base level of dollars per student and then adjusting or weighting for specific student needs (e.g., poverty, limited English proficiency, foster care, homelessness, or special education). States can also allow for local flexibility on budgeting decisions tied to identified areas of need and as determined by priority areas for continuous improvement (e.g., academic achievement, English language proficiency gains, graduation rates, chronic absenteeism, suspension rates, school climate, student access to a broad course of study, family and caregiver engagement, and access to qualified teachers). (See also Redesigning Curriculum, Instruction, Assessments, and Accountability Systems.)

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of adopting more equitable school funding formulas.

Resources

- 5 Things State Leaders Should Do to Advance Equity: State Funding Systems (The Education Trust, Fact Sheet)

- Investing for Student Success: Lessons From State School Finance Reforms (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

- Making the Grade: How Fair Is School Funding in Your State? (Education Law Center, Report)

Policy Strategy 2 Allocate Adequate Funding Across the Developmental Continuum

Evidence suggests that experiences from birth to age 5 are critical to development and that high-quality early learning opportunities lead to significant and sustained benefits for children. Investments in early childhood education programs have been found to have substantial gains in educational attainment and future earnings. A review of 21 public preschool programs found that students who attend high-quality preschool programs can experience lifelong benefits, are better prepared for school, and show greater learning gains in comparison to children who do not attend preschool. For example, a study of one of these programs, New Jersey’s Abbott Preschool Program, found that students who received 2 years of preschool showed sustained and significant achievement in 4th- and 5th-grade math, literacy, and science—far exceeding students who did not attend preschool.

Evidence suggests that experiences from birth to age 5 are critical to development and that high-quality early learning opportunities lead to significant and sustained benefits for children. Investments in early childhood education programs have been found to have substantial gains in educational attainment and future earnings. A review of 21 public preschool programs found that students who attend high-quality preschool programs can experience lifelong benefits, are better prepared for school, and show greater learning gains in comparison to children who do not attend preschool. For example, a study of one of these programs, New Jersey’s Abbott Preschool Program, found that students who received 2 years of preschool showed sustained and significant achievement in 4th- and 5th-grade math, literacy, and science—far exceeding students who did not attend preschool.

Yet many children do not have access to these opportunities due to inadequate public funding. When preschool is available, many programs run for only a few hours a day, despite research that suggests that part-day programs are less effective than full-day programs at boosting child outcomes and are inaccessible for many working families.

State support for early care and education can address opportunity gaps that exist from an early age and can have lasting positive effects on students and their families and caregivers. Yet funding inequities are especially stark when it comes to access to high-quality early learning opportunities. One report found that early childhood programs received only about 37% of the public funding needed to provide high-quality care and education. Due to the lack of public funding, families and caregivers must cover the cost of care and education, which is often too expensive for many. As a result, few infants and toddlers have access to early education and care, and just 53% of 3- to 5-year-olds attended preschool in 2017. According to a report from the Education Trust, out of the 26 states analyzed, only 1% of Latino/a children and 4% of Black children were enrolled in high-quality preschool programs.

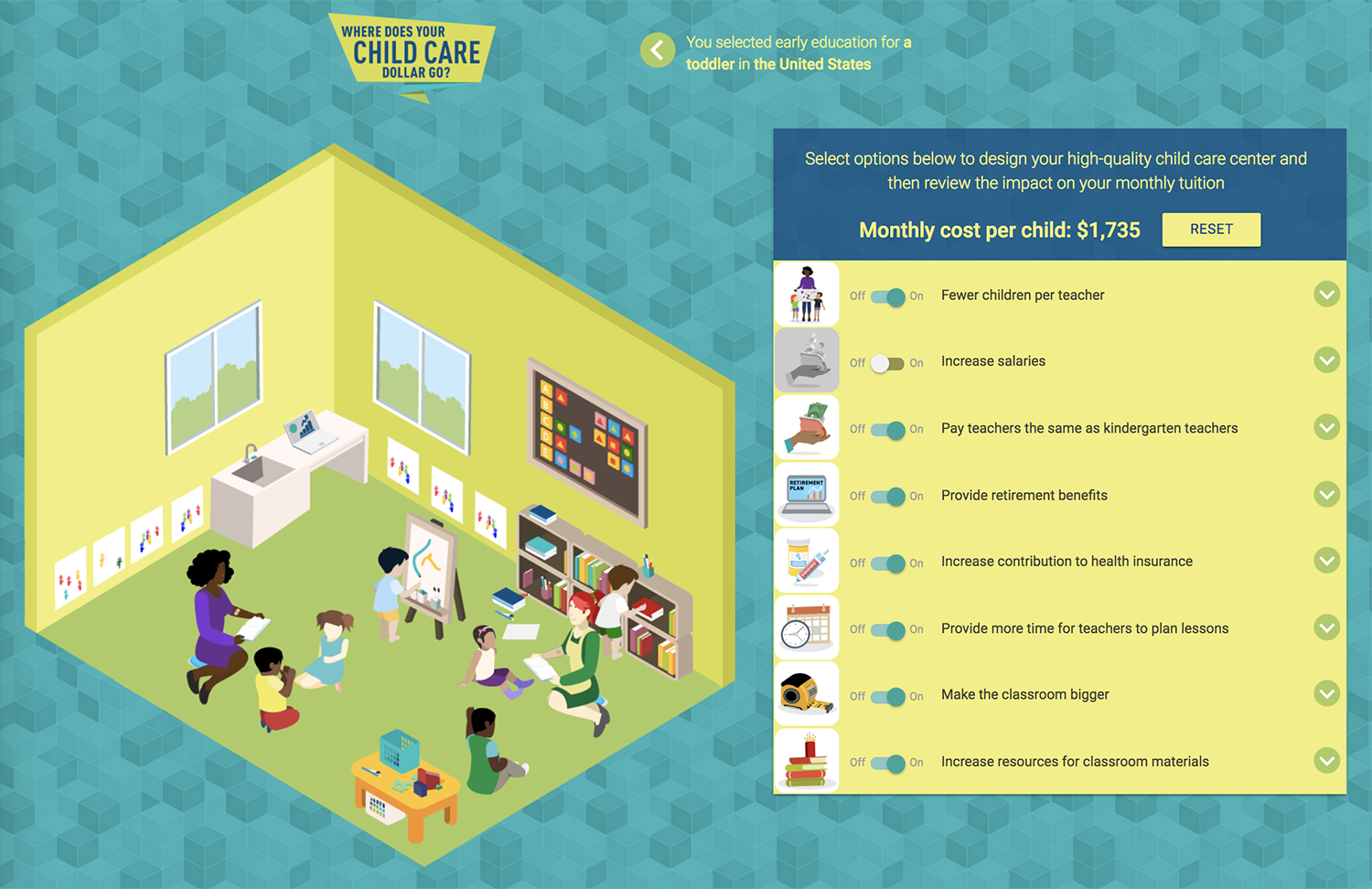

|

Where Does Your Child Care Dollar Go? CostOfChildCare.Org is a project of the Center for American Progress that explores the costs of providing quality child care. Visit the interactive. |

Policy Actions

States can allocate new funding across the developmental continuum to ensure children and families are supported from birth to age 5 by:

-

Investing in and supporting programs that allow families and caregivers and children to access high-quality early learning experiences. States can address achievement gaps early, before they widen, through investments in children from birth through kindergarten entry. For example, states can do the following:

-

Invest in prenatal health care and paid family leave

-

Support parents in accessing full-day child care

-

Invest in universal access to high-quality preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds in a way that supports socioeconomic, racial and ethnic, and linguistic diversity

-

Provide funds that are commensurate with the cost of running a high-quality program and a high-quality preschool

-

Invest in adequate compensation for the early learning workforce

States can make child care and preschool affordable using a sliding fee scale based on the ability of families and caregivers to pay for care, with full subsidies for the lowest-income families. Another key change that states can make to promote equity is adding preschool to school funding formulas. States that have done this have some of the highest enrollment in preschool or Head Start in the country. Even during recessions, state policymakers have added preschool through strategies such as the 10-year phase-in period used in West Virginia.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of allocating funding across the developmental continuum.

Resources

- Early Care and Education State Budget Actions FY 2020 (National Conference of State Legislatures, Report)

- How States Fund Pre-K: A Primer for Policymakers (Education Commission of the States, Brief)

- The Road to High-Quality Early Learning: Lessons From the States (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

Policy Strategy 3 Blend and Braid Federal, State, and Local Resources

Funds and other resources are often misaligned, fragmented, and inefficiently spent without guidance and clear structures to coordinate the numerous funding streams coming from federal, state, and local sources for children and youth, educators, and schools. Guidance and coordination can break down silos and promote data sharing and interagency cooperation, which can help ensure a more efficient and streamlined approach to distributing funds and resources across systems, accounting for their use, and meeting the varied needs of students and families. It can also help support evidence-based student support systems, such as community school models, that provide a comprehensive range of services to students and rely on state and federal funding across multiple agencies and programs.

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) provides flexibility for states and districts to use federal funding and resources in a comprehensive way, but states will need to take the lead in blending and braiding resources and modeling for localities how to do the same.

Policy Actions

States can blend and braid federal, state, and local resources to reduce fragmentation and improve alignment across programs and funding streams and can support districts in doing the same by:

-

Convening state leadership across a range of children’s issues, youth issues, and family issues to coordinate state and federal funding streams that meet the needs of children and families. This may include health and human services, economic development, education, higher education, juvenile justice and corrections, labor, and other relevant agencies that are intended to meet the holistic needs of students and families. As mentioned in Setting a Whole Child Vision: Policy Strategy 3, this can include creating a permanent children’s cabinet that meets regularly, convening a stakeholder task force to evaluate gaps in cross-sector service provision, and issuing guidance on ways state agencies can coordinate and streamline services.

-

Conducting an assessment of the available federal, state, and local resources across agencies and programs to provide a whole child support system from early childhood through adolescence and into adulthood. This may involve identifying current and new opportunities to blend and braid resources across federal and state programs (see Policy Strategy 4: Leverage and Align Federal Funds); providing support to local agencies; and clearly and proactively outlining for local agencies the available funding and the allowable uses of those funds within schools and across communities, including how whole child efforts can be integrated into existing priorities.

-

Leveraging funding to allow all preschoolers to learn in integrated settings, regardless of family income. Means testing for programs causes children to be sorted and segregated into classrooms by family or caregiver income. For example, Head Start and state preschool programs often operate in parallel and serve children in poverty separately from their peers from higher-income families in state or private preschool programs. Preschoolers with special needs in state-run preschool programs are also siloed into special education classes because preschool programs are often disconnected from school districts and lack staff with specialized training. (See Setting a Whole Child Vision for more information on coordinating, strengthening, and streamlining services.)

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of blending and braiding federal, state, and local resources.

Resources

- Coverage of Services to Promote Children’s Mental Health: Analysis of State and Insurer Non-Compliance With Current Federal Law (California Children’s Trust; Mental Health America; Well Being Trust, Report)

- Innovative Financing to Expand Services So Children Can Thrive (Children’s Funding Project; Education Redesign Lab, Brief)

- States Partnering With Educational Service Agencies to Increase Capacity, Coherence, and Equity (Council of Chief State School Officers, Guide)

Policy Strategy 4 Leverage and Align Federal Funds

There is a wide range of federal programs available that can be used to support the learning and development of children and youth, but they are spread across numerous agencies and departments. In 2003, the White House Task Force on Disadvantaged Youth laid out the fragmentation of federal resources in stark terms: 339 federal programs spread across 10 departments and agencies spending more than $225 billion each year to support underserved youth and their families, but with little coordination, alignment, or management to ensure the funds were being spent efficiently and equitably. The National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development conducted a representative scan of these programs and found a broad array of opportunities to meet whole child needs, including supports for low-performing schools and underserved students, health and wellness, bullying prevention, national service opportunities for mentors and tutors in schools, and prevention and treatment of substance abuse (see the Appendix of the Commission’s Policy Agenda for more information).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government made historic new levels of investment available to state and local governments and local educational agencies (LEAs). The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided $1.9 trillion in federal stimulus funding to help state and local governments—as well as individual taxpayers and businesses—address the impact of COVID-19. This act provided just over $170.3 billion to education, including more than $125.4 billion for k–12 public education, which made ARPA the federal government’s largest single investment in our schools. This investment added to the $13.5 billion in recovery funds for public education from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and $54.3 billion from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government made historic new levels of investment available to state and local governments and local educational agencies (LEAs). The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided $1.9 trillion in federal stimulus funding to help state and local governments—as well as individual taxpayers and businesses—address the impact of COVID-19. This act provided just over $170.3 billion to education, including more than $125.4 billion for k–12 public education, which made ARPA the federal government’s largest single investment in our schools. This investment added to the $13.5 billion in recovery funds for public education from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and $54.3 billion from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA).

States can take several important steps to ensure that communities are able to access existing funds from federal programs and agencies—including new federal recovery funds—and use these funds efficiently and effectively. For example, states can provide clear guidance on available federal resources and expertise to help local leaders align funding and manage essential partnerships to deploy resources. State leaders can also advocate for increasing flexibility in the use of funding tied to demonstrated improvement in outcomes of children and youth and more efficient compliance and reporting systems.

Policy Actions

States can leverage and align federal funds in ways that support all young people in having access to the whole child opportunities they need to succeed by:

-

Utilizing and aligning federal funding through ESSA and related legislation to make strategic investments that build local capacity and support settings designed for healthy development, especially in the most marginalized communities. For example, federal funding streams include:

-

ESSA Title I funds, which target low-income schools and can be used to address resource inequities (access to devices, wraparound services, and educational staff)

-

ESSA Title II funds, which can provide professional development for educators to build their capacities to meet the social-emotional and academic needs of students (see Building Adult Capacity and Expertise)

-

ESSA Title III funds, which can provide support for English learners and immigrant students to attain English language proficiency. These funds also support participation in language instruction programs by the parents, families, and communities of English learners

-

ESSA Title IV funds, which can be used toward a wide range of programs that support students and provide opportunities for academic enrichment, such as Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grants, School Safety National Activities, the Full-Service Community Schools program (see Policy Strategy 5: Invest in Community Schools and Integrated Student Supports), and the Education Innovation and Research program. ESSA Title IV funds may also be used to support LEAs that are implementing plans to reduce exclusionary discipline or expand access to school-based counseling and mental health programs

-

McKinney-Vento funds, which support students experiencing homelessness (SEH). These funds can be reinforced with increased state funding for SEH programs to help ensure that students receive the necessary resources for a quality educational experience. State policymakers can also guide and support districts in coordinating McKinney-Vento funds with other federal, state, and local funding streams to help them provide quality SEH programs

-

Utilizing and aligning federal funding streams from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and other federal agencies to support the well-being of children and adolescents. States can support LEAs in providing for young people’s health and wellness through, for example:

-

The expanded use of Medicaid, which can support initiatives related to health and mental health

-

The adoption of the “community eligibility provision” of the National School Lunch Program administered by the Department of Agriculture, which allows the nation’s highest-poverty schools and districts to serve breakfast and lunch at no cost to all enrolled students

-

The distribution of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Healthy Schools grants, which fund educational programming and staff development related to healthier nutrition and physical health

-

Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) grants to receive support from national service members (e.g., AmeriCorps, AmeriCorps Seniors, AmeriCorps VISTA) to address identified school and community needs

-

Investments from the Federal Communications Commission E-rate program to help close the digital divide by helping schools purchase devices and internet access (See Policy Strategy 6: Close the Digital Divide for more information.)

-

Utilizing and aligning federal k–12 funding streams to make strategic investments that support a high-quality educator workforce in high-need schools. Federal k–12 funding streams that can be used to develop and support teaching capacity include:

-

ESSA Title II funds, which can provide professional development that helps educators continually build on and refine student-centered practices that support social and emotional learning

-

Supporting Effective Educator Development (SEED) grants, which can fund training opportunities and pathways into teaching for teachers and leaders in child development and learning

-

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) funds, which fund programs and support teachers in meeting the needs of students with disabilities, including Part D funds, which can also be used for personnel preparation and development

-

Utilizing and aligning federal higher education funding streams to make strategic investments that support a high-quality educator workforce in high-need schools. To support the development of high-quality educator preparation programs, states can support institutions of higher education in accessing:

-

Higher Education Act (HEA) Title II-A Teacher Quality Partnership Grants, which can support high-quality teacher residency and school leader preparation programs

-

HEA Title III and V funds, which can support teacher preparation programs at Historically Black Colleges and Universities; Tribal Colleges and Universities; Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian–Serving Institutions; Predominantly Black Institutions; Native American–Serving, Nontribal Institutions; Asian American and Pacific Islander–Serving Institutions; and Hispanic-Serving Institutions

States can also work with institutions of higher education and the state higher education and/or student aid agencies to help ensure that they are accessing and making prospective educators aware of the following service-related federal financial aid in Title IV of the Higher Education Act:

-

Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) Grant Program, which provides scholarships of up to $4,000 per year (for up to 4 years) to undergraduate and graduate students who are preparing for a career in teaching and who commit to teaching a high-need subject in a high-poverty elementary or secondary school for 4 years

-

The Teacher Loan Forgiveness (TLF) Program, which allows teachers with certain federal loans who teach in schools of concentrated poverty for 5 consecutive years to earn $5,000 in loan cancellation. This amount can increase to $17,500 for k–12 teachers in high-poverty schools teaching special education or secondary teachers in high-poverty schools teaching math or science

-

The Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) Program, which provides loan forgiveness for a borrower’s outstanding loan balance after 10 years of full-time employment in a public service profession, such as teaching in a public school. States should help institutions of higher education work with students interested in loan forgiveness programs to determine whether TLF or PSLF is best suited for their context, including loan balance and planned service area

-

Utilizing and aligning federal career and technical education (CTE) funding streams to make strategic investments that support high-quality teacher workforces in high-need schools. Funding through the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act can be used to strengthen k–12 and postsecondary CTE programs for students, support teaching as a high school career pathway, address CTE teacher shortages, and provide for CTE educator development. CTE funding can also be used for curricular and pedagogical support, peer mentoring, and increases in the number of licensed and credentialed CTE personnel. For example, states can do the following:

-

Provide financial incentives and additional supports for individuals with industry or educational backgrounds to become certified as CTE teachers, particularly in STEM-related fields

-

Incentivize CTE teachers to earn industry- or sector-specific certifications and credentials, such as in the STEM fields or other in-demand industry sectors or occupations

-

Improve and diversify the pipeline into the CTE profession by underwriting preparation for individuals from both industry and academic backgrounds, particularly in subject-area shortage fields, for CTE positions (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information about investing in the educator workforce.)

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of leveraging federal funding.

Resources

- Federal Funding Streams and Strategies to Improve Conditions for Learning: A Resource Guide for States (Council of Chief State School Officers, Guide)

- A Guide to Expanding Medicaid-Funded School Health Services (Healthy Schools Campaign, Guide)

- Investing in Our Future: Ensuring Student Access to SEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, Video)

Policy Strategy 5 Invest in Community Schools and Integrated Student Supports

As described in Transforming Learning Environments, integrated student support systems—through multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), community schools, and/or coordination of service teams (COST)—link children and families and caregivers to a range of academic, health, and social services at the school site. As laid out in Policy Strategy 4: Leverage and Align Federal Funds, there are numerous federal opportunities to support a whole child approach to learning and development. Many of these resources can specifically be used to bolster community schools and integrated student support services.

Community schools can also be supported with federal recovery act funds, as they are an allowable use under Titles I, II, and IV of ESSA. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) specifically identifies “full-service community schools” as an allowable use of funds to support student mental health. Additionally, the 20% of local educational agency (LEA) funds set aside for learning recovery under ARPA, as well as state set-aside funds, can be used to support community schools, including by providing expanded and enriched learning time.

States play a critical role in communicating about, targeting, and coordinating federal funding streams. States can also develop their own grant programs and budget supports, technical assistance, and regulations to facilitate community school and integrated student support implementation.

Policy Actions

States can invest new or additional funding in community schools and integrated student supports to better serve the holistic needs of children and families by:

-

Developing and supporting community schools through state funding, guidance, and technical assistance. For example, states can establish grant programs or a formula-based approach to develop and support collaborative partnerships for local planning and implementation of community schools. To guide implementation, states can create guidance documents, toolkits, or FAQs describing funding sources, resources, examples, and best practices. In addition, states should provide technical assistance to connect districts with communities of practice and provide professional development. State boards of education can also issue policy resolutions to signal support for LEAs to take up a community school strategy, create common definitions, and help direct resources to support implementation.

-

Adopting and supporting evidence-based integrated student support service initiatives. This may include increasing investments in:

-

Access to lunch, breakfast, after-school, and summer meal programs

-

In-school support personnel (e.g., counselors, tutors, social workers, school psychologists, mentors) and in supporting partnerships with community mental health providers

-

Health and wellness screenings and services

-

Developing and coordinating policies that connect multiple initiatives, such as MTSS models, to meet the needs of all young people

This may also involve enlisting regional agencies to help coordinate local services (e.g., family engagement, health care, housing support, nutrition services, job support, transportation assistance), including through MTSS and Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (PBIS) implementation as well as district community school initiatives, and providing professional development, coaching, and technical assistance. (See Transforming Learning Environments, Policy Strategy 4: Establish Integrated Support Systems for more information about integrated student supports.)

-

Blending and braiding federal funding through ESSA as well as federal recovery funds with local initiatives and programs to support new or existing community school initiatives. State and local funding sources to support community school initiatives may include grant programs and formula funding as well as private and philanthropic sources. Federal funding sources may include Title I, Part A funding for school improvement in schools identified for comprehensive or targeted support and intervention and can be used to support community schools, which qualify as an evidence-based intervention under ESSA. Titles II and IV funding can be used to support whole child programs through educator professional development and the Student Support and Academic Enrichment Program. Title IV funds designated for community learning centers and full-service community schools can also be used to support community schools. Community schools can also be supported with federal recovery funds.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of community schools.

Resources

- Community Schools Playbook (Partnership for the Future of Learning, Playbook)

- Community Schools: An Evidence-Based Strategy for Equitable School Improvement (Learning Policy Institute; National Education Policy Center, Brief)

- Financing Community Schools: A Framework for Growth and Sustainability (Partnership for the Future of Learning, Brief)

Policy Strategy 6 Close the Digital Divide

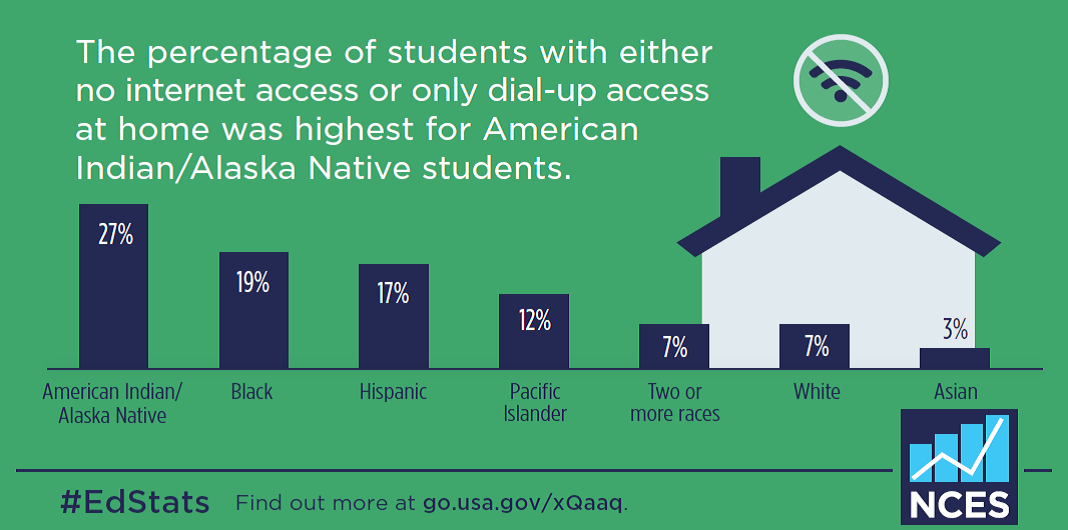

Technology and high-speed internet access are critical resources for students to succeed in school and life, yet many students lack access to reliable connectivity and appropriate technology to meet their whole child needs. According to one recent report based on data from the 2018 census, approximately 30% of the 50 million k–12 students in the United States lacked high-speed internet or devices needed for digital learning, with nearly two thirds of those students lacking both. This report also found that at least 300,000 teachers lacked adequate connectivity to teach from home. Furthermore, evidence shows that these disparities disproportionately impact students of color, students from low-income families, and students in rural communities. (See Figure 5.2.)

Source: National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). The digital divide: Differences in home internet access.

Extended periods of school closures and remote and hybrid learning caused by the COVID-19 pandemic brought greater attention to the digital divide and the urgent need to close it. A survey from spring 2020 found that 13% of parents from low-income homes reported lacking devices or internet connections and were nearly 10 times more likely than those from more affluent homes to say their children were doing little or no remote learning. Students from low-income families were also 3 times more likely to report not having consistent access to a device and 5 times more likely to attend a school without distance learning materials or activities.

Closing the digital divide is critical to addressing educational equity and providing opportunities to enhance deeper and more authentic learning. (See Redesigning Curriculum, Instruction, Assessments, and Accountability Systems for more information on deeper learning skills and instruction.) In addition to being essential for learning, connectivity also provides families with access to telehealth, employment, and other needed benefits. One report estimated that closing the digital divide will require at least $6 billion for infrastructure and devices at the federal level, half being recurring costs each year. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) makes a one-time down payment toward closing this divide by providing $7.2 billion in funding through the newly created Emergency Connectivity Fund, which can be used to provide devices and connectivity to students, educators, and patrons of public libraries, but ongoing funding through the federal E-Rate program will be needed to ensure long-term digital connectivity for all students.

Policy Actions

States can close the digital divide to ensure every child has access to appropriate technology and connectivity, and its effective use, to meet their whole child needs by:

-

Creating plans to ensure every child has access to computing devices and internet. States may need to survey districts to gain a better understanding of where students experience barriers to accessing devices or high-speed internet. States and districts should create task forces or working groups to inform actionable plans so all students can access high-speed internet connections with up-to-date devices. These plans should be designed in partnership with the community, state agencies, and businesses to provide technology that is equally accessible for historically underserved children, including students with disabilities and English learners. In addition, such plans may include guidance and technical assistance to facilitate implementation.

-

Leveraging federal and state programs that can supplement district budgets to ensure equitable access to computing devices and internet connectivity. For example, states may supplement funding from the federal E-rate program to expand broadband access or utilize funding from COVID-19 relief packages to purchase laptops. To ensure all students have high-speed internet access and access to up-to-date devices, states should prioritize schools in underserved areas farthest from reliable internet access, including those in low-income rural communities.

-

Facilitating partnerships between districts and nonprofit or for-profit businesses to alleviate the costs of expanding broadband to unserved and underserved students in the districts. For example, states can advocate for the private sector (network providers and device manufacturers) to offer discounted and consistent pricing across all districts to ensure equitable access to districts regardless of purchasing power. States can also build partnerships and leverage more funding for targeted internet expansion in schools by connecting these efforts to other policy priorities—economic development, transportation, health care, and agriculture.

-

Investing in professional development for educators to ensure the effective use of technology. States should ensure that educators have access to high-quality professional development on effectively using and integrating technology into classroom instruction in ways that are guided by teacher and student needs and that include peer-to-peer collaboration. Such professional development may include micro-credentials, self-guided modules, or online certificates. Professional development should also be provided to support staff, such as guidance for counselors, social workers, and nurses, to help them effectively deliver services remotely.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of closing the digital divide.

Resources

- Broadband Access and the Digital Divides (Education Commission of the States, Brief)

- Close the Digital Divide (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

- How States Are Expanding Broadband Access (The Pew Charitable Trusts, Report)