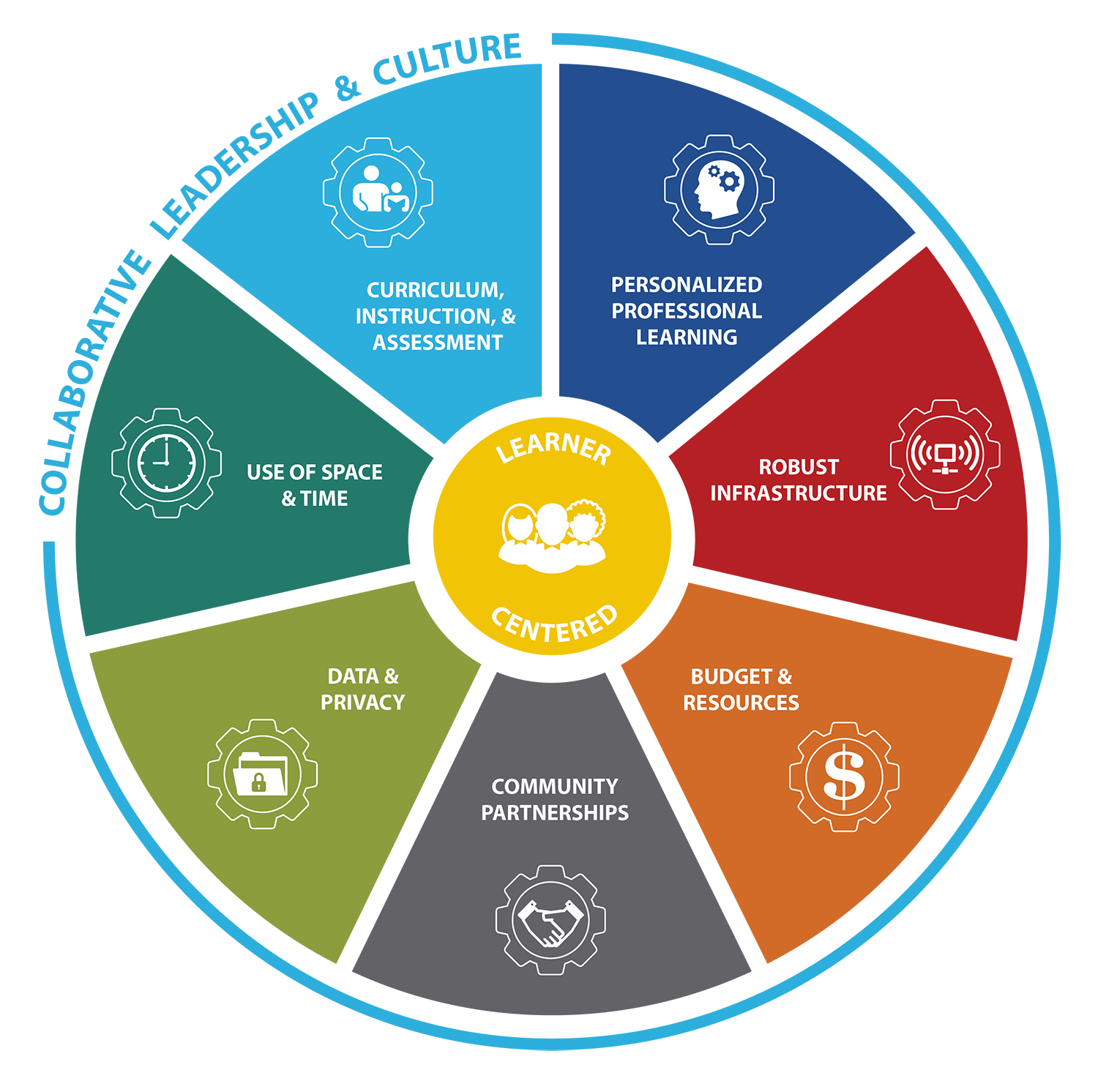

Redesigning Curriculum, Instruction, Assessments, and Accountability Systems

Why a Redesign of Curriculum, Instruction, Assessments, and Accountability Is Needed

The U.S. education system remains substantially reliant on the factory model of education designed during the Industrial Revolution, in which teachers deliver instruction to passive students, content areas are siloed, and learning can be primarily defined by summative test scores. This model stands in stark contrast to the growing knowledge base of how people learn: through authentic learning experiences that actively engage students, develop higher-order thinking skills, ask students to apply what they have learned, and treat all students as equally capable of success. Research also shows that people learn by connecting new information to what they already know and understand and by being able to draw on their cultural experiences and community contexts. It also shows that people need opportunities to receive real-time feedback and to reflect on their learning in meaningful ways. These findings suggest that curriculum, instruction, and assessments should build upon children’s prior knowledge and be culturally and linguistically responsive; support conceptual understanding, engagement, and motivation; and develop students’ metacognitive skills, agency, and capacity for strategic thinking.

Supporting schools in creating these types of learning experiences will require a reshaping of curriculum, instruction, assessment, and accountability systems. As discussed in Transforming Learning Environments, it will also require building relationship-centered, identity-safe schools; establishing restorative and educative approaches to discipline; and providing integrated student supports and expanded learning time. To reshape these systems, states can do the following:

-

1Promote rich learning experiences that provide challenging curriculum in all content areas and support the development of deeper learning skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and social-emotional competencies; and draw on culturally and linguistically responsive approaches

-

2Support authentic systems of assessment that are culturally and linguistically responsive, provide students with opportunities to demonstrate their learning and development in a variety of ways, and are designed to measure growth and progress

-

3Adopt a comprehensive accountability system designed for continuous improvement that includes indicators of students’ opportunities to learn, the quality of teaching and learning experiences, students’ contexts and school climates, and how well they are prepared for postsecondary success

-

4Strengthen distance and blended learning models that are equity focused, offer personalized instruction, and take advantage of the different settings in which learning can take place

Policy Strategy 1 Promote Rich Learning Experiences

Rich learning experiences foster student motivation through complex content knowledge development and tasks that hold value to the student and a focus on setting and achieving learning goals. They provide students with opportunities to deeply understand disciplinary content through both direct instruction and opportunities to engage in discipline-specific models of inquiry (e.g., scientific investigation, mathematical modeling, literary analysis, historical inquiry, or artistic performance). They also develop students’ beliefs in their abilities to succeed through appropriately challenging activities and well-designed and implemented progressions of lessons to guide students in tasks that go beyond their existing knowledge bases or skill sets. Rich learning experiences also provide opportunities to develop students’ metacognitive skills—the ability to reflect on learning processes and understanding—and enable students to start and persist at tasks, recognize learning patterns, evaluate their own learning strategies, evaluate what works, and invest adequate effort to succeed and to transfer knowledge and skills to increasingly complex problems. A substantial body of research has found that students who employ metacognitive strategies, including self-regulated learning and goal setting, are better able to engage in cognitive processes, remember information, and maximize learning.

Ensuring students have access to these learning experiences supports the development of:

-

Productive mindsets that enable perseverance and resilience, especially a growth mindset

-

Executive functioning that supports planning, organizing, problem-solving, and self-management

-

Interpersonal and communication skills that support collaboration and enable students to describe their academic work and learning and their growth in character

-

Reflective mindsets and skills that enable students to evaluate personal strengths, challenges, and progress toward goals

-

Compassionate and civic mindsets that encourage students to treat others with kindness, celebrate different identities, and contribute positively to their communities

As Table 3.1 suggests, teaching in the ways that children learn will, in many ways, require reimagining the purpose of and approach to schooling. Schools that are designed to unleash the potential within every child have replaced the standardized assembly line with greater personalization, grounded in the knowledge that each child’s identity, cultural background, developmental path, interests, and learning needs create a unique path for that child. Students engage in collaborative inquiry-based learning by pursuing questions and problems that matter to them and to their communities. Rather than memorizing facts and regurgitating them on a test, students synthesize existing knowledge, apply it to open-ended questions and complex problems, and create something of value for an authentic audience beyond school.

|

Transforming from a school with … |

Toward a school with … |

|

Transmission teaching of disconnected facts |

Inquiry into meaningful problems that connect areas of learning |

|

A focus on memorization and recall of facts and formulas |

A focus on deep understanding of concepts and applications of learning |

|

An exclusive emphasis on standardized materials, pacing, and modes of learning |

Strategies that allow multiple pathways for learning and demonstrating knowledge |

|

A view that students are motivated—or not |

An understanding that students are motivated by engaging tasks that are well supported |

|

A focus only on individual work; consulting with others is considered “cheating” |

A focus on collaborative as well as individual work; consulting with others is a major resource for learning |

|

Curricula and instruction rooted only in a canonical view of the dominant culture |

Curricula and instruction that are culturally responsive, building substantially on students’ experiences |

|

Tracking systems based on the view that ability is fixed and requires differential curriculum |

Heterogeneous grouping, based on the understanding that ability is developed in rich learning environments |

Source: Adapted from Learning Policy Institute & Turnaround for Children. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action.

Rich learning experiences provide all students exposure to instruction in complex academic content in all discipline areas, as well as opportunities to engage in (1) inquiry-based learning, (2) culturally responsive pedagogy, (3) social and emotional learning, and (4) inclusive heterogeneous grouping.

Inquiry-based learning—which involves questioning, considering possibilities and alternatives, and applying knowledge—requires students to take an active role in constructing their own knowledge as they work to solve a problem or probe a question. Inquiry-based instruction incorporates students’ exploration of a problem with direct instruction that supports their efforts to find answers to questions that illuminate core concepts in a domain. The inquiry process includes opportunities for students to explain and discuss their thinking so that educators can determine what additional instruction or resources are needed to guide a constructive learning process.

Project-based learning is one form of inquiry learning that develops students’ knowledge and skills while they investigate meaningful problems or answer a complex question. Projects often center on real-world issues; incorporate interdisciplinary and standards-based tasks related to scientific or historical inquiry, close reading and extensive writing, and quantitative modeling and reasoning; and often require students to present their work publicly. Studies on project-based learning find that students exposed to this kind of curriculum do as well as or better than their peers on traditional standardized test measures and significantly better on measures of higher-order thinking skills that transfer to new situations. Students participating in project-based learning also exhibit stronger motivation, improved problem-solving ability, and more positive attitudes toward learning.

The development of these skills can also be accomplished through civic engagement opportunities (e.g., volunteering, national service, service-learning projects), internships, career shadowing and mentoring, career and technical education experiences, and independent studies.

Schools that offer rich learning experiences incorporate instructional strategies that build on students’ experiences and affirm students’ cultural and linguistic histories as they connect new learning to prior knowledge. A person’s culture ranges from concrete elements members of a community share, such as food, holidays, dress, music, and language, to less observable, collectively held beliefs and norms. Culturally responsive pedagogy is critical because “the brain uses cultural information to turn everyday happenings into meaningful events.” Bringing students’ cultural contexts into schools and classrooms supports an approach to education that recognizes the value and potential all students bring to the classroom. Culturally responsive curricula and teaching build on and validate students’ diverse experiences to support learning, engagement, and identity development. Culturally responsive learning environments celebrate the unique identities of all students while building on their diverse experiences to support rich and inclusive learning. (See Transforming Learning Environments for additional information on identity-safe and relationship-centered environments.)

As culturally responsive, sustaining, and affirming pedagogical approaches center and celebrate diversity, they further belonging and inclusion and positively affect educational outcomes, including engagement in learning and academic achievement. Furthermore, students from all backgrounds benefit from inclusive learning environments that honor and celebrate diversity. These settings not only can help all young people learn about and embrace the diverse backgrounds and cultures that make up the fabric of U.S. democracy but can also cultivate their awareness and orientations toward issues of fairness and inclusion.

Ensuring that young people have rich learning experiences also requires culturally responsive content and materials that:

-

Reflect and respect the legitimacy of different cultures

-

Empower students to value and learn from other cultures, in addition to their own

-

Incorporate information from many cultures into the heart of the curriculum, instead of only on the margins

-

Relate new information to students’ life experiences

For students to become engaged and effective learners, educators must simultaneously develop content-specific knowledge and cognitive, social, and emotional skills. These skills include executive functions, a growth mindset, social awareness, resilience and perseverance, metacognition, curiosity, and self-direction. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for additional information on culturally and linguistically responsive teaching.)

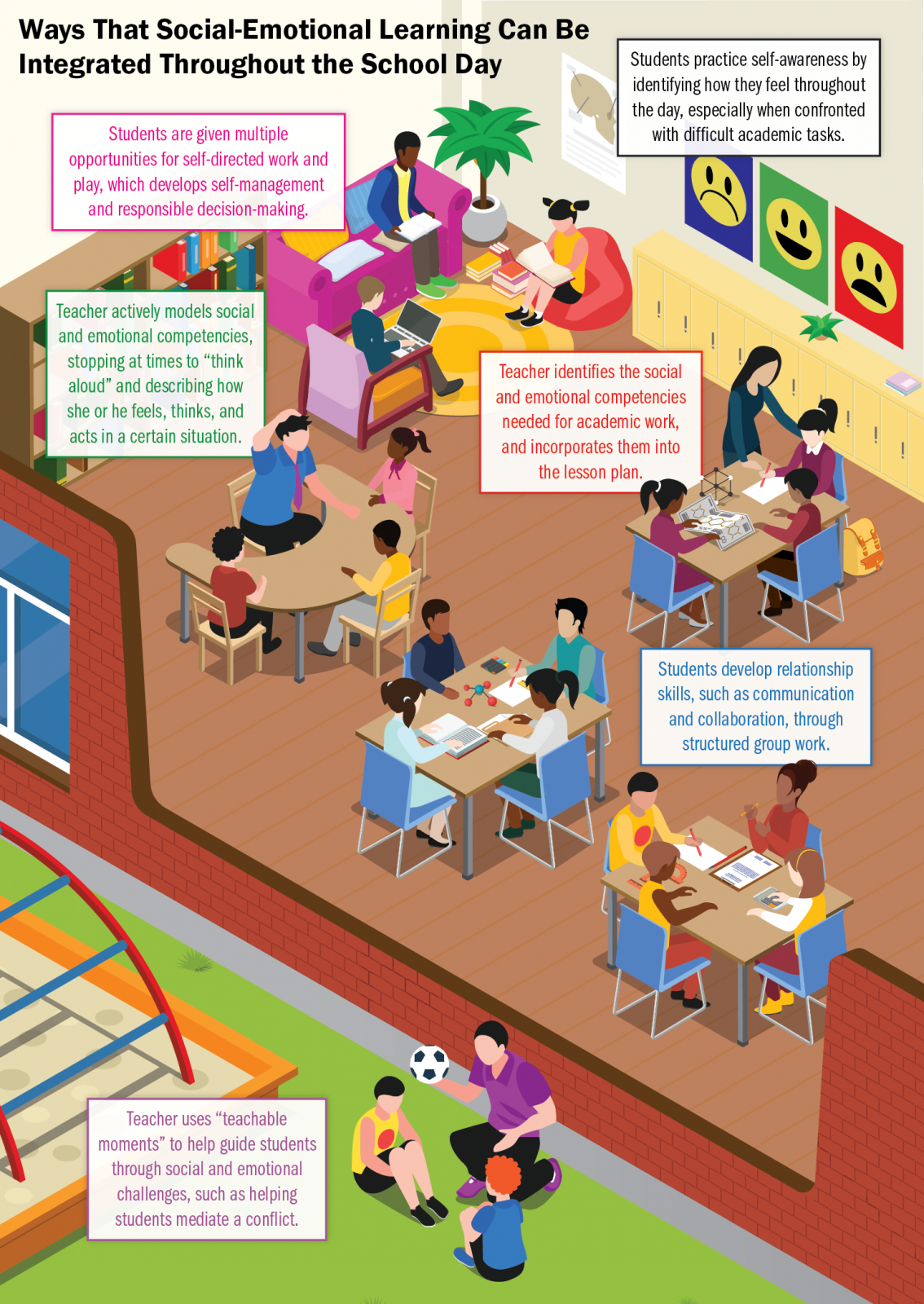

To ensure students have the opportunity to learn and practice cognitive, social, and emotional skills, schools need to be supported in dedicating consistent time—either within a given curriculum or in the school day—to the development of those skills. Studies show that students who engage in social and emotional learning programs demonstrate improvements in their social-emotional skills; attitudes about themselves, others, and school; social and classroom behavior; and outcome measures like test scores and school grades. A meta-analysis of over 200 studies found that students in social-emotional learning programs experienced reductions in misbehavior, aggression, stress, and depression and significant increases in achievement. A second meta-analysis found that these benefits were sustained in the long term, showing how learned attitudes, skills, and behaviors can endure and serve as a protective factor over time. Social-emotional learning programming has also been found to have an 11-to-1 return on investment.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) framework has been used by many states to develop social-emotional learning standards. (See Figure 3.1.)

Source: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2020). CASEL’s SEL framework: What are the core competence areas and where are they promoted?

It is important to avoid equity pitfalls in adopting and implementing social-emotional learning standards and curricula. Educators must be provided with guidance and resources that emphasize student agency and the assets they possess and can develop, rather than identifying students’ deficits. In addition, it is important that leaders and educators understand and appreciate the similarities and differences in cultural expressions of cognitive, social, and emotional competencies. For example, in some cultures, it is considered inappropriate for a child to look an adult in the eye, whereas in others, it is considered a sign of respect. Without an understanding of various cultural norms, practitioners may mistakenly assume some students do not display or embrace certain skills, habits, or mindsets.

Further, it is also important to recognize that stand-alone social-emotional learning curricula, while useful, are insufficient to develop the needed skills, habits, and mindsets when such practices are not actively modeled by adults, incorporated throughout the school day—during classes, lunchtime, recess, and extracurriculars, as well as in disciplinary policies and practices—and integrated into these routines in ways that are culturally affirming and relevant. (See Figure 3.2.) Integration of these skills in ways that develop long-term habits can help eliminate the view that some students need to be “repaired” and ensure that equity is at the center of these practices.

Source: Melnick, H., & Martinez, L. (2019). Preparing teachers to support social and emotional learning: A case study of San Jose State University and Lakewood Elementary School. Learning Policy Institute.

Exclusionary practices, such as tracking mechanisms that exclude students from curricula and coursework focused on higher-order skills, communicate differential worth to students and undermine achievement. Decades of research show that tracking can harm students by reducing achievement for those limited to low-level curricula.

To the greatest extent possible, learning environments should promote inclusive approaches within heterogenous classrooms, strategically creating small groups for targeted instructional support when needed, and differentiating instruction to meet student needs.

Policy Actions

States can promote and support the development of rich learning experiences by:

-

Investing in the development and adoption of the high-quality curriculum frameworks, instructional materials, assessments, and professional development that support higher-order thinking and inquiry-based learning in all content areas; culturally and linguistically responsive curriculum and instruction; and integrated SEL. States can further support schools and districts by establishing an online hub that provides access to resources for high-quality curriculum, instruction, and assessments (see Policy Strategy 2: Support Authentic Systems of Assessment) in the academic disciplines that support deeper learning.

-

Developing school and district capacity to pilot learning experiences that promote the development of productive habits and mindsets (e.g., executive function, intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, collaboration, conflict resolution, a growth mindset, agency over learning). For example, states can invest in and support high school learning experiences that include opportunities for applied learning and personalized pathways (e.g., internships, career shadowing, career technical education courses, independent studies, community service projects). States can also consider developing competency-based curricula and course sequencing, personalized learning plans, and mastery-based learning progressions. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information on preparing educators to support personalized learning.)

-

Eliminating policies and practices that promote early tracking (pre-k–8) and replacing them with practices that ensure all students have access to rich learning experiences. This can include:

-

Providing guidance and support to help schools adopt more inclusive approaches, such as creating temporary small groups for targeted instructional support, engaging in high-intensity tutoring, and adapting lessons to accommodate students at different levels

-

Supporting schools implementing differentiated instruction through the provision or recommendation of high-quality curricular tools and professional development for teachers

-

Examining data on student access to advanced courses and high-quality career and technical education pathways and addressing any issues that are surfaced by the data

-

Establishing competencies for social, emotional, and cognitive learning that clarify both the social-emotional skills students should develop and the practices that best support development of those skills. States have used statements of competencies and standards as well as professional development funding to inform teacher practice, provide guidance to school and district administrators, and empower parents and families to support social-emotional learning at home.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of rich learning experiences.

Resources

- A Process for Developing and Articulating Learning Goals or Competencies for Social and Emotional Learning (American Institutes for Research; Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, Guide)

- Social and Emotional Learning and Development, Conditions for Learning, and Whole Child Supports in ESSA State Plans (Council of Chief State School Officers; EducationCounsel, Brief)

- The State Education Agency’s Role in Supporting Equitable Student-Centered Learning (Council of Chief State School Officers, Guide)

Policy Strategy 2 Support Authentic Systems of Assessment

Authentic systems of assessment, focused on student growth and progress, help educators understand how to leverage instruction to support learning and help students develop a deeper understanding of concepts. When students feel supported to grow and reflect on their efforts, instead of being compared to others, they are more likely to believe they can improve their performance with time and effort. Assessments that focus on growth can increase students’ motivation and engagement. In contrast, researchers have found that comparison-oriented assessments lead students to have a decreased interest in school, to disengage from learning environments, and to experience a lowered sense of self-confidence and efficacy.

Authentic systems of assessment, focused on student growth and progress, help educators understand how to leverage instruction to support learning and help students develop a deeper understanding of concepts. When students feel supported to grow and reflect on their efforts, instead of being compared to others, they are more likely to believe they can improve their performance with time and effort. Assessments that focus on growth can increase students’ motivation and engagement. In contrast, researchers have found that comparison-oriented assessments lead students to have a decreased interest in school, to disengage from learning environments, and to experience a lowered sense of self-confidence and efficacy.

Schools and teachers need both the time and tools to assess whole child needs and establish clear goals for the types of assessments they use. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information on supports for educators to implement authentic assessments.) While states have largely focused on end-of-year, summative assessments to gauge school and student performance, educators need support in developing diagnostic and formative assessment processes, embedded in the instructional context, to identify student understanding and provide feedback in real time, adapt curriculum and instruction, and allow students to demonstrate learning through authentic, mastery-based tasks.

|

What Are Formative and Diagnostic Assessments?

Experts identify three primary goals of assessments:

Formative assessment, or assessment for learning, is carried out as part of the instructional process for the purpose of adapting instruction to improve learning. Formative assessment is contrasted with summative assessment, which measures the outcomes of learning that has already occurred.

Diagnostic assessment is a particular type of formative assessment intended to help teachers identify students’ specific knowledge, skills, and understanding in order to build on each student’s strengths and specific needs. Because of their domain specificity and design, diagnostic tools can guide curriculum planning in more specific ways than most summative assessments.

Combined with insights from diagnostic assessments that help teachers identify students’ current thinking and chart next steps, formative assessment processes allow students and teachers to monitor and adjust learning together, in real time, as they progress along an identified path.

Formative assessment processes provide feedback both to the teacher and the learner; the feedback is then used to adjust ongoing teaching and learning strategies to improve students’ attainment of curricular learning targets or goals on a day-to-day and minute-to-minute basis. Formative assessment processes are fundamentally grounded in relationships, providing participatory ways for students and teachers to attend to the full set of student experiences. These processes are linked to instruction and designed to support growth, as suggested in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2

Formative Assessment Processes

Source: Adapted from Darling-Hammond, L., Schachner, A., & Edgerton, A. K. (with Badrinarayan, A., Cardichon, J., Cookson, P. W., Jr., Griffith, M., Klevan, S., Maier, A., Martinez, M., Melnick, H., Truong, N., & Wojcikiewicz, S.). (2020). Restarting and reinventing school: Learning in the time of COVID and beyond. Learning Policy Institute. |

Educators also need access to high-quality diagnostic and formative assessment tools that pinpoint student thinking relative to learning progressions and provide actionable guidance over time for how to move students along. It is essential that the assessments used give students the opportunity to make their thinking—and not just right or wrong answers—visible and that they include careful interpretation guidance that helps teachers and students understand which next steps in learning will move student thinking forward. State and local leaders should consider assessments that include performance tasks—which teachers can build upon and modify to suit their needs—as well as reports on individual student progress relative to multiyear learning progressions rather than reports with a focus on percentile scores and rankings. States can work with schools and districts to develop three key types of assessments: (1) early childhood assessments, (2) performance assessments, and (3) locally constructed assessments.

Across the nation, assessments are increasingly being used to measure children’s competencies from preschool to 3rd grade. High-quality early childhood assessments, when well designed and well implemented, can support developmentally appropriate early learning experiences by providing valuable information to guide instruction and support whole child development.

While some states use common early childhood assessments during preschool, many states begin assessing children’s skills and knowledge with a kindergarten entry assessment (KEA). When a KEA fits into an early childhood assessment system, starting in preschool and continuing into the early elementary grades, it can help provide educators and policymakers with an understanding of how children are progressing over time so that they can guide instruction and make investments to support learning. However, the inappropriate use of KEAs or other early childhood assessments for placement or enrollment decisions can have unintended consequences by perpetuating inequities, especially if they inaccurately measure the abilities of groups of children (e.g., children who are dual language learners, children with special needs, and children from diverse cultural backgrounds).

Research suggests that effective assessments of children in early learning classrooms have specific features. Assessments should be authentic and appropriate for the assessed age groups and populations, including children with diverse cultures, languages, or special needs. Assessments should also cover the five key aspects of development—social-emotional development, cognitive development, language and literacy development, mathematical and scientific reasoning, and physical development—to inform instructional strategies and program planning. High-quality assessments provide valuable information for both educators and policymakers to support the diverse range of students’ strengths and needs and address inequitable opportunities early on. For policy, aggregate data at the community and state levels can reveal inequities in access to quality early childhood resources and can inform investments that promote equity in early childhood and the early grades. Such data are especially informative if they are part of a comprehensive data system that spans early childhood and early elementary grades.

Performance assessments are often a key element of inquiry-based tasks. Such assessments require demonstrations of knowledge and skills as they are used in the real world. Students are typically asked to apply their knowledge and skills in creating a paper, project, product, presentation, and/or demonstration. These may be assembled and communicated through student portfolios or the systematic collection of student work samples, records of observation, scored papers or products, and other artifacts collected over time to evaluate growth and achievement.

Performance assessments encourage higher-order thinking, evaluation, synthesis, and deductive and inductive reasoning while requiring students to demonstrate understanding. Furthermore, performance assessments can provide multiple entry points for diverse learners, including English learners and students with special needs, to access content and display learning. The assessments themselves are learning tools that also build students’ co-cognitive skills, such as planning, organizing, and other aspects of executive functioning; resilience and perseverance in the face of challenges; and a growth mindset, which develops from the ongoing process of fine-tuning and improving the product. A growing number of schools and districts organize high school work around a portfolio of performance tasks that are assembled and exhibited to demonstrate the competencies they expect graduates to have developed.

There are several ways states can support authentic performance-based assessments within state assessment systems. For example, one way to include these components is through curriculum-embedded performance assessments, which are implemented in the classroom during the school year and may extend over days or weeks. This approach offers several benefits, including the following:

-

More completely assessing college and career-ready standards, including independent and collaborative student-initiated research and inquiry; the ability to take and use feedback productively; and oral, written, and multimedia communication

-

Evaluating higher-order skills, such as the analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and application of knowledge to complex problems

-

Better reflecting how learning is applied in real-world settings and thus strengthening validity

-

Creating greater curriculum equity for students by using assessments to create strong units and instructional practices across classrooms, rather than having only some students experience instruction for deeper learning

-

Increasing teachers’ understanding of the standards and of high-quality teaching and assessment by involving them in developing, reviewing, and scoring tasks

Student learning is deeply connected to local contexts—the scope and sequence of courses a district is pursuing, the curriculum teachers are using, and the in- and out-of-classroom experiences students are having. Therefore, compared with a single statewide assessment, locally relevant assessments can more accurately identify what students are learning and can better inform local decisions made on teaching and learning. Locally constructed assessments can also be more culturally and linguistically responsive than one-size-fits-all assessments, allowing educators to adapt as needed to meet students’ needs and support their ongoing learning.

As part of a system of authentic assessments, schools also need tools to understand how students, teachers, staff, and families and caregivers experience the school environment. Research shows that students learn more effectively in environments in which they feel safe and supported, that well-supported teachers lead to better student outcomes, and that building relational trust with families and caregivers is essential to supporting long-term school improvement. One important tool that many states and districts are using is climate surveys to gauge various dimensions of the learning environment, including safety and belonging, teaching and learning, interpersonal relationships, and engagement, and then using that survey data to make improvements. (See Transforming Learning Environments for more information on how this can be accomplished.)

Policy Actions

States can support the design and implementation of authentic formative assessments that support growth and reflection by:

-

Adopting high-quality, developmentally appropriate early childhood assessments that shine a light on children’s needs and abilities from preschool through early elementary grades. Assessments should consider key domains of child development (e.g., social-emotional development, cognitive development, language and literacy development, mathematical and scientific reasoning, and physical development) to plan instruction tailored to students’ needs, track progress over time, and make appropriate demands of young children. States should support educators and administrators in understanding the purpose of the assessment, how to effectively administer state tools, and how to use the data to inform instruction and work with families and caregivers. States can also use assessment data to identify opportunity gaps and strategically fund initiatives that strengthen early learning systems.

-

Supporting and centering authentic performance-based assessments within statewide initiatives. States’ assessment efforts should include performance-based tasks that evaluate higher-order thinking and deeper learning—aligned with state standards—to measure and incentivize high-quality and equitable teaching and learning practices in k–12. One way states can encourage this is to allow districts to use performance-based assessments to demonstrate readiness to graduate. States can support districts in using performance-based assessments by developing resources that might include:

-

Extended-response performance tasks that are part of on-demand assessments (e.g., in statewide summative assessments)

-

Libraries of performance assessments that are developed and vetted by the state or its educators and are made available statewide across grade levels and content areas (and may have some administration requirement, such as being part of a statewide interim assessment system)

-

A set of classroom-embedded assessment tasks that are intentionally aligned with tasks on statewide assessments

-

Model curriculum units and frameworks with embedded assessment tasks and formative processes

States should also consider providing supports for effective use of any state-developed or recommended resources, including multilingual translations, valid and informative rubrics and score reports, documents showing connections to standards and competencies, suggestions for instructional moves based on student performance, and guidance for adapting materials to be more supportive of specific diverse learner communities (e.g., attending to local context, cultural and linguistic diversity, special needs, and student interest and identity).

-

Supporting schools and districts in adopting, developing, and using high-quality local assessments designed to equitably measure student growth and progress. Balanced, coherent, and authentic systems of assessment require that local assessment efforts—those that are adopted, developed, and used at the district, school, and classroom levels—are performance-based; are aligned with both standards and learning progressions; and provide the range of information educators, students, families, and leaders need to support student learning. States can support these efforts by:

-

Sharing tools and resources to support quality assessment selection, development, and use for different purposes (e.g., common rubrics, quality criteria)

-

Publishing exemplar assessments and vetted recommendations for technical assistance providers and assessment instruments

-

Providing professional learning opportunities for school and district leaders as well as educators (e.g., workshops for development and use, professional learning for student work analysis, training for scoring performance-based assessments)

-

Enabling innovative local efforts through waivers for innovation zones, funding for local assessment initiatives, and pathways for local assessment efforts to lead to meaningful credentials for students

-

Sharing guidance for high-quality local assessment data practices and policies (e.g., equitable grading, advancement and access to advanced courses, etc.)

-

Providing support for validating locally developed assessments

It is important that states provide both guidance and guardrails that intentionally ensure that local assessments maintain a high bar for quality while attending to the wide range of data needs of educators and students, including diagnostic information, just-in-time formative feedback, progress and growth information, and performance and achievement data for individual students as well as disaggregated student groups.

-

Supporting and incentivizing educator professional learning and capacity-building related to effective assessment use to support student learning, growth, and achievement. This can include:

-

Leading professional learning workshops, communities of practice, and educator leadership development initiatives and institutes focused on not only assessment development and implementation but also meaningful data practices within classrooms, schools, and districts

-

Partnering with key professional learning and technical assistance providers

-

Connecting educator professional learning to ongoing state initiatives (e.g., assessment or curriculum development efforts, training on the use of model resources and curricula, and other content-specific initiatives)

States should consider including a substantial professional learning component in applications for federal and foundation assessment support.

-

Supporting schools and districts in using multiple data measures to evaluate school context, student achievement, and opportunities to learn. As part of a system of authentic assessments, states can include multiple measures that they factor into student success in their school accountability and continuous improvement plans that can include:

-

Collecting school climate data (e.g., student, staff, and family surveys; student attendance and engagement data; discipline data; student perceptions of their SEL competencies)

-

Leveraging extended performance-based tasks (e.g., project-, community-, and work-based learning assessments) to measure deeper learning and character competencies, such as collaboration, communication, perseverance, etc.

-

Surveying for opportunity-to-learn (OTL) considerations (See Policy Strategy 3: Adopt a Comprehensive Accountability System for Continuous Improvement for more on OTL measures.)

-

Providing guidance and professional development on the use of universal screening tools for social, emotional, and behavioral health issues to monitor students throughout the school year and connect them to needed supports

These data, like all other data, should be disaggregated by student groups to identify and address any disparities and analyze how different groups of students may be experiencing school.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of authentic assessments.

Resources

- Developing and Measuring Higher Order Skills: Models for State Performance Assessment Systems (Learning Policy Institute; Council of Chief State School Officers, Report)

- Formative Assessment and Next-Generation Assessment Systems: Are We Losing an Opportunity? (Council of Chief State School Officers, Report)

- High-Quality Early Childhood Assessment: Learning From States’ Use of Kindergarten Entry Assessments (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

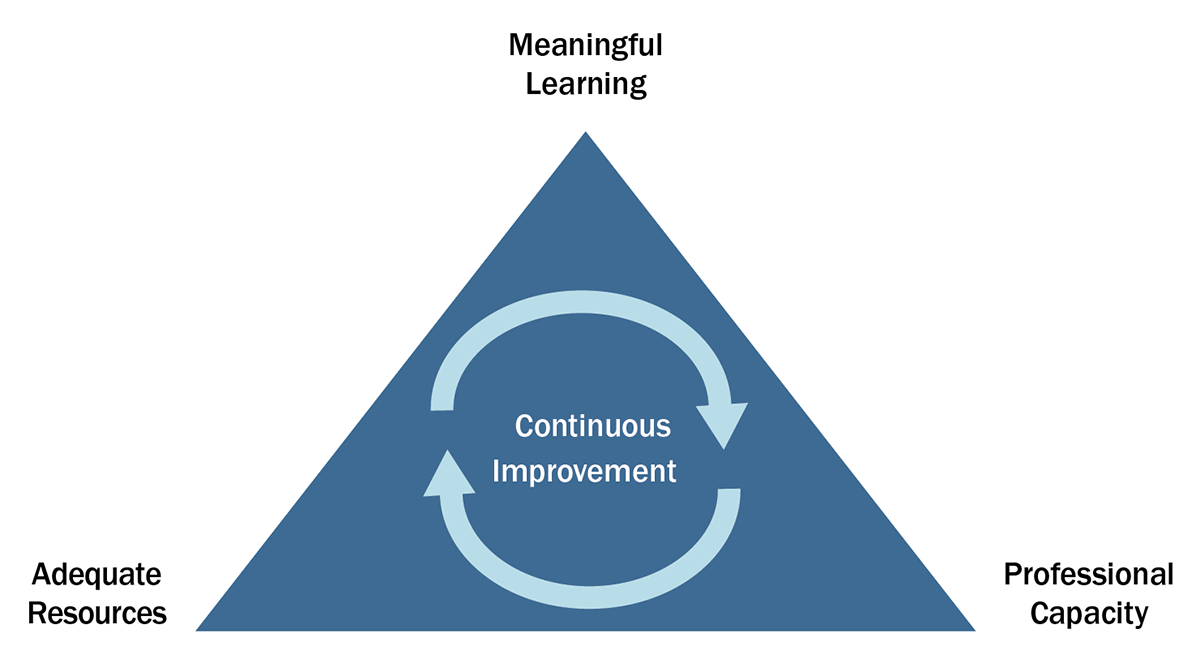

Policy Strategy 3 Adopt a Comprehensive Accountability System for Continuous Improvement

Effective accountability and improvement systems set expectations for performance and provide adequate support in three key, related domains: (1) a focus on meaningful learning enabled by (2) professionally skilled and committed educators and supported by (3) adequate and appropriate resources. (See Figure 3.3.) Such systems move away from a single-score model of evaluation to a more comprehensive approach using multiple measures, such as a dashboard model. Like a dashboard on a car, which provides indicators of speed, distance traveled, fuel, tire pressure, and other information that allows the driver to diagnose how things are working, a school dashboard can provide a wide range of useful state and local indicators and include mechanisms for state monitoring of what schools and districts are doing and to what effect. These approaches allow the means for identifying and intervening when support is needed and provide useful information to the public to assess the quality of schools.

Source: Adapted from Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., & Pittenger, L. (2014). Accountability for college and career readiness: Developing a new paradigm. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

Comprehensive accountability systems are built on the assumption that student outcome data are insufficient for informing improvement and that accountability systems should instead focus on both the performance of the system and the conditions and/or opportunities underlying that performance. A 2019 National Academy of Sciences report, Monitoring Educational Equity, calls for a system of educational equity relying on two sets of indicators that measure (1) disparities in attainment outcomes and engagement in schooling and (2) equitable access to resources and opportunities.

For example, Monitoring Educational Equity suggests 16 indicators in 7 key domains:

-

Kindergarten readiness (e.g., disparities in reading and literacy, numeracy and math skills, and self-regulation and attention skills)

-

K–12 learning and engagement (e.g., disparities in attendance and absenteeism, accumulating credits, GPA, and achievement and growth on assessments)

-

Educational attainment (e.g., disparities in on-time graduation, enrollment in college, entry into the workforce, or military enlistment)

-

Extent of racial, ethnic, and economic segregation (e.g., concentration of poverty in schools and racial segregation within and across schools)

-

Equitable access to high-quality early learning programs (e.g., disparities in the availability of and participation in licensed pre-k programs)

-

Equitable access to high-quality curricula and instruction (e.g., disparities in teacher experience, certification, and diversity; availability and enrollment in advanced coursework and gifted and talented programs; availability and enrollment in arts, sciences, social sciences, and technology courses; and access to and participation in formalized systems of tutoring and other academic support services)

-

Equitable access to supportive school and classroom environments (e.g., disparities in students’ perceptions of safety, academic support, teacher–student trust; out-of-school suspensions and expulsions; and supports for emotional, behavioral, mental, and physical health)

Further, effective accountability and improvement systems should be built on three principles: (1) shared accountability, (2) adaptive improvement, and (3) informational significance. Shared accountability requires that all stakeholders willingly take on collective responsibility for the accountability system and work together for the continuous improvement and success of all students. Adaptive improvement acknowledges that school capacities differ greatly and that effective accountability and improvement systems require flexibility that is responsive to school and community conditions. Finally, accountability systems should provide information that is significant to inform and enable school improvement. They should provide a mix of state direction and support, including identifying where additional resources might be needed, and provide oversight. They should provide this alongside the local autonomy needed to align state and local goals and priorities, strengthen governance, and provide schools and districts the flexibility they need to serve their communities effectively. At best, they allow communities and a broader group of stakeholders to help determine how funds should be spent. (See Investing Resources Equitably and Efficiently for more information on leveraging multiple funding streams.)

To be most effective, accountability systems that support improvement also require comprehensive and diagnostic data and supports for educators for using the data in decisions. These two tools help educators and leaders at all levels understand and use data to inform practice, select the appropriate strategy or intervention, and evaluate whether progress is being made.

Policy Actions

States can adopt a comprehensive accountability system that measures students’ opportunities to learn and supports a system of continuous improvement toward whole child opportunities and outcomes by:

-

Adopting a broad set of indicators in their statewide accountability and improvement systems that reflect student opportunities for learning and encourage shared responsibility for student outcomes. These indicators can be used for different purposes—reporting out publicly, addressing disparities, identifying schools for support and intervention, and informing the selection of supports and interventions. States can adopt indicators of educational attainment and engagement to include:

-

Kindergarten readiness

-

Attendance and absenteeism rates

-

State assessment achievement and growth data

-

English language proficiency gains

-

On-time and extended-year graduation rates (e.g., 5–7 years)

-

College and career readiness based on courses and programs completed

-

Civic readiness based on evidence of civic engagement

-

Postsecondary enrollment rates or rates of entry into the workforce or military

Accountability systems may also include indicators of equitable access to resources and opportunities, such as:

-

Access to high-quality early learning programs

-

Access to high-quality courses, instruction, and curriculum, including advanced courses

-

Suspension and expulsion rates

-

Access to a safe and supportive school climate

-

Access to well-prepared educators

-

Access to resources (e.g., devices, curricular and instructional materials, internet)

-

Fiscal equity

-

The extent of racial, ethnic, and economic segregation

-

Access to expanded learning opportunities

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), states are required to report information included in their statewide accountability systems by student status, including by race and ethnicity, economic disadvantage, and language and special education status, to illustrate where there are inequities that should be addressed. In so doing, information from these indicators can be leveraged by states and districts to guide school improvement efforts. States can also encourage cross-tabulation across student groups (e.g., by race and gender) and disaggregation of college- and career-readiness measures by student group and pathway. States currently have to disaggregate assessment and graduation-rate data for students experiencing homelessness and foster care for reporting purposes. States should consider disaggregating for these groups across all indicators given the unique needs and growth of this population, especially as a result of the pandemic and economic downturn.

-

Ensuring that districts, schools, educators, families, and students have ongoing access to student opportunity and outcome data to improve learning environments in a user-friendly format. States may consider using dashboards for many of their indicators to allow for a more comprehensive view of district and school progress and performance across multiple indicators (e.g., academic achievement, English language proficiency gains, graduation rates, chronic absenteeism, suspension rates, school climate surveys, student access to a broad course of study, parent and family engagement, access to qualified teachers). By providing access to a broad array of data points, states can also set up a process for informed local decision-making for continuous improvement. This process should include regular examination of data indicators by district and school staff and local stakeholders to identify and reward areas of growth and to tie in planning and budgeting decisions to provide support (e.g., funding, state and county assistance, increased staffing capacity, additional resources) on indicators in need of improvement. This would allow for the strategic and timely use of data by educators and support staff and allow them to monitor the effectiveness of selected strategies and interventions.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of accountability systems.

Resources

- Accountability for College and Career Readiness: Developing a New Paradigm (Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education, Report)

- Evolving Coherent Systems of Accountability for Next Generation Learning: A Decision Framework (Council of Chief State School Officers, Framework)

- Making ESSA’s Equity Promise Real: State Strategies to Close the Opportunity Gap (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

Policy Strategy 4 Strengthen Distance and Blended Learning Models

In many ways, COVID-19 has highlighted and exacerbated existing inequities in our education system, including access to high-speed internet and technology. (See Investing Resources Equitably and Efficiently for more information about closing the digital divide.) As policymakers decide how to effectively support learning now and in the future, it is critical to implement high-quality distance and blended learning models that support authentic learning with equity in mind. The current environment has also increased calls for a change in how learning is structured, particularly for redefining attendance from time spent in class to time students are engaged in learning.

Distance and blended learning models offer a combination of face-to-face and online instruction, with the goal of providing an integrated and authentic learning experience. Research on distance and blended learning has found that well-designed online or blended instruction can be as or more effective than in-classroom learning alone. This research also emphasizes that the way in which blended learning is designed and facilitated matters for effectiveness. For example, in-person and online instruction should be combined in strategic ways that allow students to control how they engage with online learning. High-quality blended and virtual learning models include experiences that provide frequent, direct, and meaningful interactions that focus on solving problems and developing ideas. They also use interactive materials and offer opportunities for feedback, revision, and instruction in self-management strategies. Ultimately, in- and out-of-school learning needs to be connected and seamless, with tasks chosen to take advantage of the different settings in which learning will take place during and after the pandemic.

To promote the effective use of technology, educators must have the training and support to be able to implement high-quality distance and blended learning models. During and after our current emergency, educators will continue to be the most important factor in student learning—wherever that learning may occur. Research shows that investments in professional development, when well designed and effectively implemented, lead to improvements in teacher practice and student outcomes. The COVID-19 pandemic, and its impact on state and local resources, highlights the need to support states and districts in building long-term capacity to meet unforeseen challenges to student learning. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more on preparing educators to support distance and blended learning.)

Policy Actions

States can strengthen distance and blended learning models by:

-

Supporting districts and schools with standards, guidance, models, training, and materials designed to increase student engagement in distance and blended learning. For example, states can support students’ and teachers’ use of technology and digital tools by developing digital learning standards that articulate how technology can empower learners and support high-quality distance and blended learning models.

-

Supporting states, districts, and schools in collecting data to guide decisions to ensure all students have access to devices and the internet. This may include surveying the extent to which students and educators have access to high-speed internet and devices. Based on the needs from these surveys, states, districts, and schools should leverage federal resources to support increased access. Access to the internet and devices could also be used as an indicator in statewide accountability systems to ensure continued focus on identifying and closing gaps.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of distance and blended learning.

Resources

- Remote Learning in Early Childhood (National Association of State Boards of Education, Brief)

- Restart and Recovery: Considerations for Teaching and Learning (Council of Chief State School Officers, Guide)

- Strengthen Distance and Blended Learning (Learning Policy Institute, Report)