Setting a Whole Child Vision

Why States Need to Set a Whole Child Vision

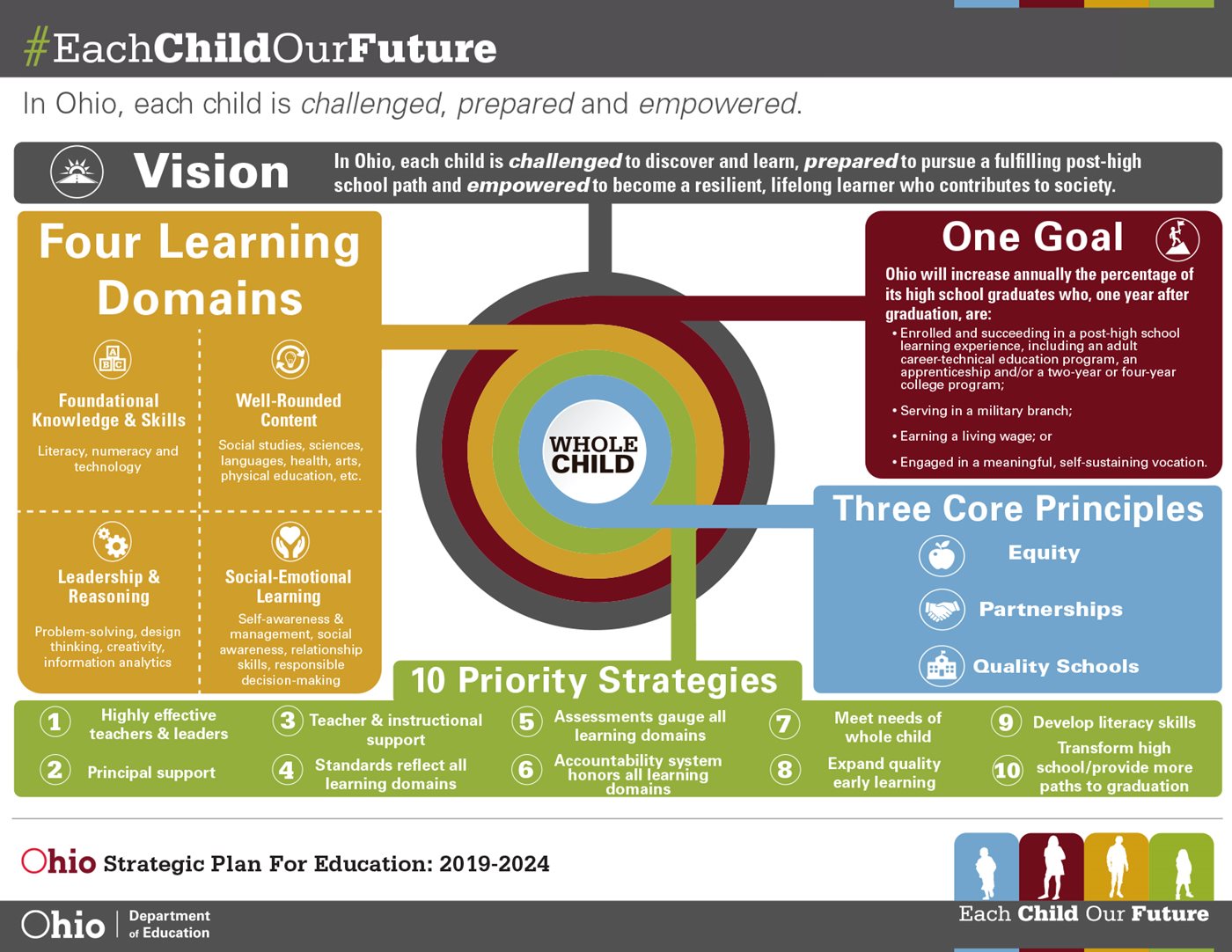

Improving educational and life outcomes for young people must be guided by a clear, coherent vision that articulates the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students need to be successful and how state and local leaders will provide the resources to ensure students are able to succeed. A shared whole child vision, created by a diverse, representative set of stakeholders, is essential for communicating the need for a systemic, collaborative approach to meeting the needs of every child.

A whole child vision can also deter states from advancing policy affecting children and youth in a piecemeal manner. When various agencies and educational entities work separately, this can lead to inefficiencies, redundancies, and at worst, policies that directly contradict one another. In contrast, a shared vision that has broad stakeholder buy-in provides clear direction for state policymakers in developing and adopting legislation, budgets, guidance, and regulations and in analyzing existing policies and practices for alignment with the vision. A clear, coherent vision sets a precedent for cross-agency coordination, streamlining of services, and the creation of shared learning opportunities to more effectively support children and youth.

A statewide whole child vision, tied to a statewide data system that measures both system inputs (e.g., funding, access to pre-k, high-quality academic curricula and supports, effective teaching, and expanded learning opportunities) and youth outcomes, can also provide a necessary tool for policymakers to assess existing systemic inequities and develop plans to erase them.

To set a whole child vision, states can do the following:

-

1 Convene a diverse set of stakeholders to develop a statewide whole child vision

-

2 Assess conditions for learning and development for children and youth

-

3 Establish coordinating bodies to advance the whole child vision through children and youth cabinets and strategic task forces to identify current state capacity and needs and provide guidance to support service provision

Policy Strategy 1 Convene a Diverse Set of Stakeholders to Develop a Statewide Whole Child Vision

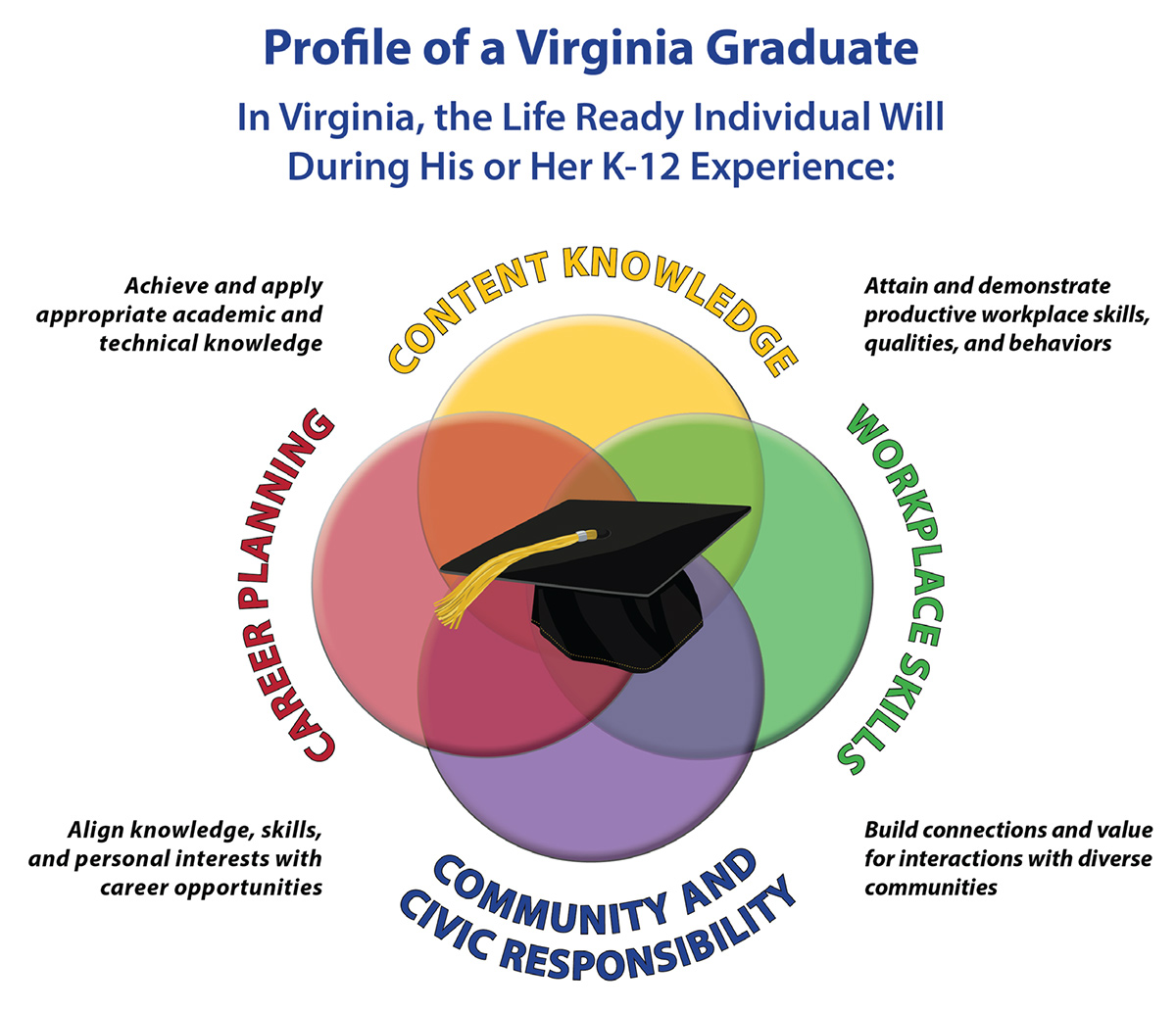

The core purpose of setting a shared whole child vision is to broaden the definition of both student and system success and establish a foundation for policy and practice in the state. The vision should (1) articulate the knowledge, skills, and dispositions young people need and (2) create a roadmap for distributing resources and support to ensure all young people can reach their full potential. A shared whole child vision communicates to all stakeholders the need for a comprehensive and collaborative approach to serving young people adequately and equitably.

A statewide whole child vision can also signal to districts and schools the importance of focusing on the whole child in their priorities and can empower communities to develop learning experiences and opportunities that will help young people meet science-backed developmental goals. At the local level, many school districts and individual schools may already have a mission statement that articulates a definition for student success and a high-level vision for establishing a learning environment to support students in achieving it. States can learn from these locally crafted statements and engage stakeholders in developing a statewide whole child vision that is grounded in the local context.

Policy Actions

States can develop and set a whole child vision for the state by:

-

Convening and engaging stakeholders across the youth-serving ecosystem to develop a shared whole child vision. State leaders such as governors or chief state school officers can convene stakeholders across agencies and youth-serving organizations. Convenings can take the form of listening tours, surveys, or meetings to gather input from stakeholders. These stakeholders should include:

-

State officials from education, health, housing, juvenile justice, social services, and other agencies working with young people

-

Legislators

-

State board of education members

-

Tribal agencies

-

Community leaders

-

After-school and youth development professionals

-

Child care providers

-

Institutions of higher education

-

Superintendents, principals, teachers, students, and families and caregivers

-

States should prioritize including historically marginalized communities to ensure their perspectives are part of the decision-making process.

-

Developing a whole child vision for learning and development. The vision or strategic plan should be grounded in the science of learning and development and provide a roadmap to supporting young people from birth to adulthood, including elements of:

-

Academic development

-

Cognitive development

-

Social-emotional development

-

Identity development

-

Ethical and moral development

-

Mental health

-

Physical health

States can develop statewide developmental goals and competencies for children as part of the vision that clearly lay out expected student outcomes. Stakeholders might consider the orientations, skills, habits, and mindsets of a successful 24-year-old in their state or what a successful high school graduate should know and be able to do. Convened stakeholders can also consider the creation of a strategic plan for distributing resources, developing partnerships, and evaluating progress toward achieving the vision.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of creating a whole child vision.

Resources

- Educating the Whole Child: Improving School Climate to Support Student Success (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

- From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope: Recommendations From the National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development (National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, Report)

- Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Framework)

Policy Strategy 2 Assess Conditions for Learning and Development for Children and Youth

A statewide whole child vision can provide a roadmap for assessing the learning and developmental conditions of children and youth and can be a tool for ensuring adequate and equitable resource distribution. Once a needs assessment has been conducted, states can create a plan of action to track and evaluate progress toward meeting identified needs and achieving the vision. The plan can establish roles and responsibilities for state agencies and stakeholder organizations; steps for implementing the vision; and timelines and processes for publicly reporting progress.

A statewide whole child vision can provide a roadmap for assessing the learning and developmental conditions of children and youth and can be a tool for ensuring adequate and equitable resource distribution. Once a needs assessment has been conducted, states can create a plan of action to track and evaluate progress toward meeting identified needs and achieving the vision. The plan can establish roles and responsibilities for state agencies and stakeholder organizations; steps for implementing the vision; and timelines and processes for publicly reporting progress.

States can also invest in a statewide data system that compiles data on children’s well-being and opportunities to learn. Many states have statewide longitudinal data systems in place, but these systems largely focus on student performance outputs (e.g., standardized test scores, graduation rates, college enrollment and retention, employment). While these data are important, data systems should also include a more holistic set of indicators, including system inputs and student opportunities, to ensure all children are supported from birth through adulthood.

To accomplish this, states may need to convene permanent or short-term governing bodies, such as a child and youth cabinet or strategic task forces (see Policy Strategy 3: Establish Coordinating Bodies to Advance the Whole Child Vision) and invest in coaching and other supports for state policymakers, educators, and youth-serving professionals on data collection, analysis, and use for continuous improvement.

Policy Actions

States can inventory existing policies and practices for alignment with the whole child vision by:

-

Conducting a needs assessment to identify current conditions for children and youth and to determine capacity to provide needed resources and services. A needs assessment provides a systemic approach to identifying the needs of children and youth across the state and evaluating state and local capacity for meeting those needs. For the needs assessment, states can collect demographic and publicly available data, conduct interviews and focus groups to collect stakeholder input, and use targeted and focused data collection methods, including surveys and other measurement tools.

-

Creating an action plan to ensure the whole child vision gets realized. States can task convened stakeholders to create a strategic action plan for meeting the vision, including roles and responsibilities, implementation guidance, timelines, and communication plans for reporting progress. States can also consider establishing indicators of short- and long-term goals that measure progress toward meeting children’s needs and assessing impact on young people’s opportunities and outcomes.

-

Establishing and investing in a statewide data system that spans cradle to career, including indicators of engagement and opportunities to learn, such as measures of:

-

School climate and culture, such as discipline and chronic absenteeism data, and access to rich learning experiences and opportunities inside and outside the traditional school day

-

Equitable access to certified and experienced educators and other measures of educator quality

-

Access to technology and virtual learning opportunities

-

Measures of fiscal equity that can reveal any disparities in access by race, gender, English learner and special education status, and other student characteristics (See Redesigning Curriculum, Instruction, Assessment, and Accountability Systems for more on opportunity-to-learn indicators.)

States could develop data collection procedures that provide unified reporting on states’ early childhood education availability and quality, as well as the compensation and qualifications of the workforce, and integrate multiple early childhood data systems with each other and with k–12 data. Further, states should be transparent and engage youth, families, and communities in developing data systems, collection, analysis, and use to ensure trust in data systems across stakeholders.

-

Providing information, time, coaching, and other support for educators, other youth-serving professionals, and state agency staff on data collection, analysis, and use. This may include using needs assessment data to identify and align interventions for both individual student and schoolwide needs. In addition, state agencies may need to coordinate to find time for recurring check-ins to validate data and share best practices.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of assessing conditions for learning for children and youth.

Resources

- 50-State Comparison: Statewide Longitudinal Data Systems (Education Commission of the States, State Scan)

- Data Quality Campaign’s Data Use Resources (Data Quality Campaign, Webpage)

- Making ESSA’s Equity Promise Real: State Strategies to Close the Opportunity Gap (Learning Policy Institute, Report)

Policy Strategy 3 Establish Coordinating Bodies to Advance the Whole Child Vision

With various agencies and institutions involved in setting policy that affects children and youth and their families and caregivers, it is far too easy for miscommunication, conflicting policies, and inefficient service provision to be the norm. For example, the early childhood education (ECE) “system” is made up of a patchwork of programs in most states, with several federal and state agencies overseeing these programs. (See Figure 1.1.) The complexity at the federal level is passed down to state administrators who often lack the capacity or authority to untangle the web of funding and requirements. This is further complicated by state programs that have their own income eligibility, quality standards, and monitoring. The incoherence of this fragmented system inhibits efforts to address ECE needs, access, and quality at the federal, state, and local levels. (See Investing Resources Equitably and Efficiently for more information on aligning ECE programs.) This fragmentation also causes disconnects in all youth-serving systems—k–12, out-of-school time, health, and others—that have led to wasteful spending and missed opportunities to meet the needs of children and youth more adequately.

Note: This chart was designed to show administrative complexity in the state of California. Some organizational changes have been made at the federal and state levels since its initial design.

Source: Melnick, H., Ali, T. T., Gardner, M., Maier, A., & Wechsler, M. (2017). Understanding California’s early care and education system. Learning Policy Institute.

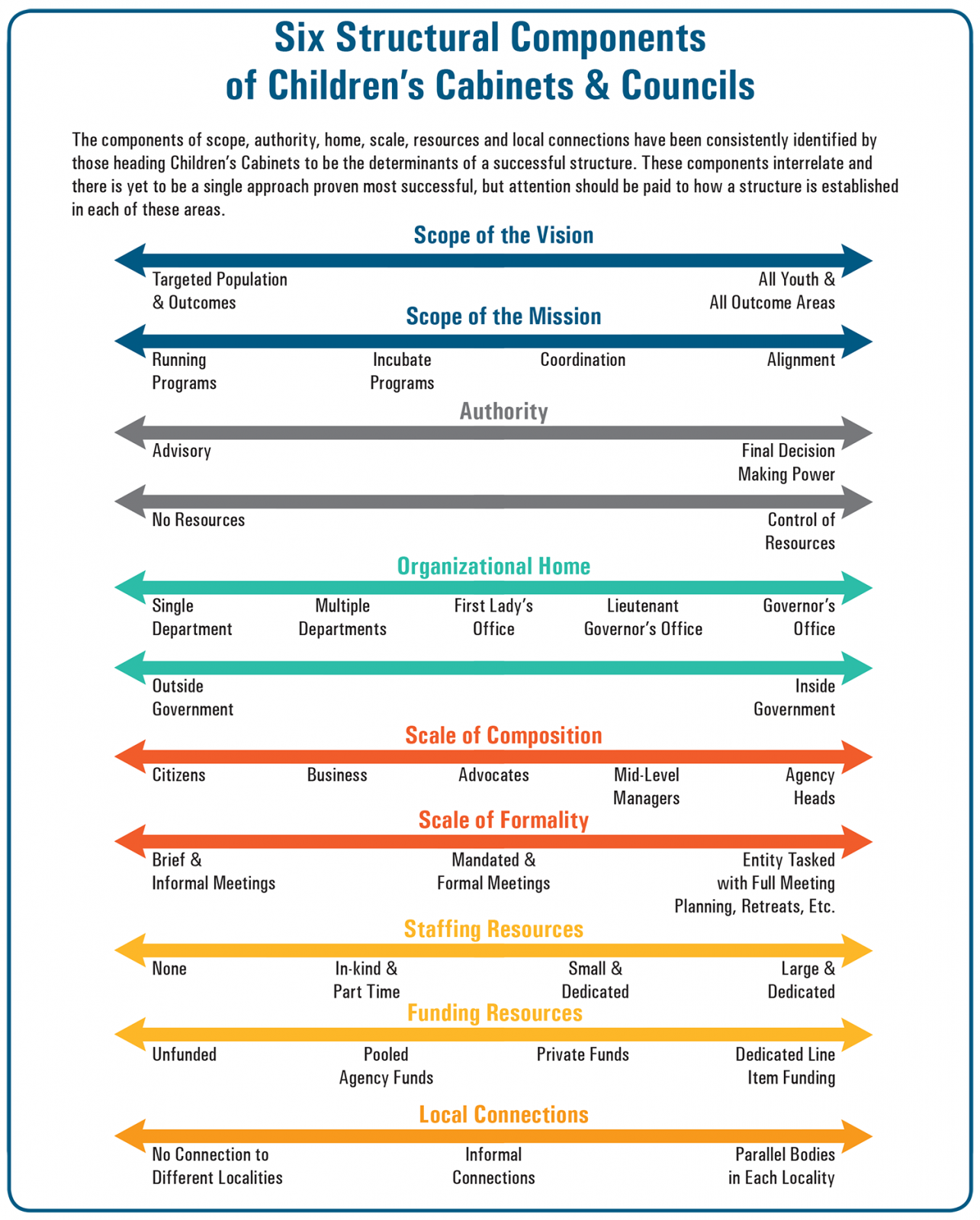

Thus, a foundational piece of effectively carrying forward the shared whole child vision at all levels of leadership is to take a coordinated and collaborative approach to decision-making and service provision. One means by which state leaders can do this is to use their convening power to bring diverse stakeholders together to address necessary changes through permanent bodies, such as a state children and youth cabinet. Children and youth cabinets, often brought together by the governor, bring together heads of government agencies (e.g., education, health and human services, housing, child welfare, transportation, labor, juvenile justice, tribal) with the goal of facilitating a comprehensive approach to serving children and youth, strengthening partnerships, and assessing and improving overall coordination and efficiency across state and local government agencies. (See Figure 1.2.) A Forum for Youth Investment report on the need for big-picture structural changes lays out several attributes of creating a well-structured and staffed children’s cabinet:

-

The opportunity to promote and institutionalize a common vision

-

The capacity to engage all stakeholders

-

The capacity to assume shared accountability

-

The authority to align policies and resources; increase public will and demand; engage young people and their families; and improve the quality, quantity, and coordination of service delivery

States can also encourage community-focused local children’s cabinets to improve local leadership coordination and service provision.

Source: Gaines, E., Faigley, I., Pittman, K. (2008). Elements of Success 1: Structural options [State Children’s Cabinet and Councils Series]. Forum for Youth Investment.

Policy Actions

States can establish coordinating bodies to advance the whole child vision by:

-

Convening leadership across a range of children, youth, and family issues. This may include leaders from health and human services, economic development, education, higher education, transportation, housing, child welfare, juvenile justice and corrections, labor, tribal nations, and other relevant agencies to identify and advance ways to better serve young people holistically. For example, the state can do the following:

-

Create a permanent children and youth cabinet that meets regularly and is staffed by at least one fully dedicated full-time equivalent employee

-

Convene a stakeholder task force to evaluate gaps in cross-sector service provision

-

Create standing advisory bodies—including youth councils—to offer ongoing support and problem-solving

-

Issue guidance on ways state and local agencies can coordinate and streamline services

-

Identify and invest in a state-level governing body, if needed, with the authority and expertise to coordinate children and youth programs, including programs for children from birth through school age

-

Establish cross-agency data sharing to better identify and meet child, youth, and family needs equitably

-

Develop cross-agency initiatives and budget proposals to support alignment

States should prioritize including youth and family voices in these governmental bodies to ensure their perspectives are part of the decision-making process.

-

Convening short-term task forces to study and make recommendations on areas of need. In addition to permanent state structures, the state can also convene diverse stakeholder organizations and agencies to address targeted areas of need and develop and strengthen targeted elements of a high-quality, equitable education system. Stakeholders might include early childhood educators, expanded learning providers, health and mental health providers, higher education institutions, and research institutions. For example, as described in the state examples, Oklahoma created a task force on trauma-informed care, while North Dakota created one on behavioral health.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of collaboration across agencies and within communities.

Resources

- 2020 State Policy Survey: Child & Youth Policy Coordinating Bodies in the United States (The Forum for Youth Investment, Report)

- Building Partnerships in Support of Where, When, & How Learning Happens (National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, Brief)

- Setting the Right Conditions for Learning: How State Leaders and Partners Can Work Together to Meet the Comprehensive Needs of Students (Council of Chief State School Officers, Report)