Transforming Learning Environments

Why States Need to Transform Learning Environments

The science of learning and development emphasizes the need for whole child learning environments that foster positive developmental relationships between students, educators, and families and caregivers. However, our current education system often minimizes opportunities to build and maintain meaningful relationships and fails to provide personalized supports that enable students to learn, cope, and become resilient. This depersonalized approach is especially damaging to students who may be experiencing the effects of poverty, trauma, discrimination, and racism. Strong relationships and restorative practices are ways to address experiences that may interfere with learning, undermine connections, and impede opportunities to grow and develop the skills and competencies young people need to succeed in school and life.

For healthy learning and development to take place, students must feel safe and supported across all domains of development—academic, cognitive, social-emotional, ethical, identity, and physical and mental health. This is more likely to happen when learning environments are structured in ways that support the whole child and are responsive to students’ strengths and needs.

To accomplish this, states can do the following:

-

1Support relationship-centered learning environments that facilitate relational trust between students, staff, and families/caregivers

-

2Foster safe and inclusive learning environments, in which all students feel valued and in which positive relationships can be created

-

3Adopt restorative and educative approaches to discipline that replace exclusionary practices with trauma-informed and healing-oriented approaches

-

4Establish integrated support systems that use an asset-based approach to address social, emotional, academic, and physical and mental health needs; develop partnerships; and provide individualized supports that meet the holistic needs of students and their families and caregivers

-

5Provide high-quality expanded learning time that mitigates opportunity gaps, builds upon students’ strengths, and nurtures positive relationships

Policy Strategy 1 Support Relationship-Centered Learning Environments

Research shows that relationship-centered learning environments must attend to (1) personalizing relationships with students, (2) supporting relationships among staff, and (3) building relationships with families and communities. As policymakers seek to support schools in improving learning environments, they must focus on all three to ensure the greatest impact.

Relationships are essential to healthy learning and development. Research has found that a stable relationship with at least one caring adult can mediate the effects of even serious adversity. Positive teacher–student and other adult–student relationships contribute to many aspects of learning and development, including better performance and engagement and greater social competence and willingness to take on challenges. All students can benefit from nurturing relationships with teachers and other adults, which can increase student learning and support their development and wellness, especially when these relationships are culturally sensitive and responsive.

School structures and practices can support the development of nurturing relationships between students and teachers as well as other school staff. Structures and practices that allow for consistency in relationships and routines and that reduce anxiety and support development include:

-

Block scheduling, which allows more time for learning and smaller pupil loads for teachers

-

Small school size and small learning communities

-

Looping, which allows teachers to stay with students for more than one year

-

Longer grade spans (i.e., k–8 or 6–12) that reduce the number of school-to-school transitions

-

Advisory systems that ensure each child and family will be well known and supported in secondary schools

-

Preschool transition plans that help kindergarten teachers support each learner as soon as they enter kindergarten

Research has found that structures and practices such as these, which allow teachers to build deeper and more consistent relationships with a small group of students, can have significant positive effects on student outcomes. For example, small schools or small learning communities with personalized structures, such as advisory systems or looping with the same teachers over 2 years or more, have been found to improve student achievement, attachment, attitudes toward school, behavior, motivation, and graduation rates.

A positive and supportive staff culture is the foundation of a school climate that enables positive developmental relationships with students. Student culture follows staff culture. Research on teacher effectiveness shows that teachers become more effective over time in collegial settings in which they have opportunities to collaborate with and learn from one another. School leaders need to prioritize structures and practices that build a healthy professional learning community for staff—supporting staff to strengthen personal relationships and collaborate effectively—and to continue their own professional and personal growth. It also requires ongoing efforts to be sure everyone on the staff feels respected, heard, and valued. Structures that help cultivate positive relationships among school staff include staff collaboration within and across disciplines, such as grade-level or subject-matter teams; dedicated time for professional learning; and opportunities to participate in shared decision-making with school leaders. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information on creating and maintaining professional and collaborative relationship-centered learning environments.)

Fostering positive, trusting relationships between school staff and families and caregivers is another critical component of student success and sustaining change and improvement. Building this kind of trust requires skillful school leaders and staff who actively listen to concerns, avoid arbitrary actions, and nurture authentic parent and family engagement and partnerships to promote student growth.

Schools that succeed in engaging families embrace a philosophy of partnership in which power and responsibility are shared. (See Figure 2.1.) It is important to recognize that when trust has been violated in a community—for instance, as a result of racial injustices or incidents of police violence—it must be rebuilt through a proactive, authentic process that includes extensive listening, relationship-building, and demonstrations that school staff are trustworthy.

Source: Mapp, K. L., & Bergman, E. (2019). Dual capacity–building framework for family–school partnerships (Version 2).

Schools can cultivate partnerships and relational trust with families and caregivers by using culturally and linguistically responsive approaches to relationship-building with families and caregivers as part of the core approach to education. These strategies may include planning teacher time for virtual or in-person home visits; teacher–parent–student conferences to learn from parents about their children; meetings and school events flexibly scheduled around parents’ availability; and culturally and linguistically appropriate outreach to families, including regular communication through positive phone calls, emails, and text messages.

Policy Actions

States can support districts and schools in redesigning learning environments in ways that prioritize strong, stable relationships between students, staff, and families and caregivers by:

-

Rethinking policies and providing guidance on removing impediments to and supports for relationship-centered school designs, including staffing structures. States can do the following:

-

Encourage the redesign of schools by rethinking staffing designs and ratios embedded in state and local policies

-

Support districts in adopting and implementing flexible master scheduling, which can allow for the creation of allocated and consistent relationship-centered structures, including block scheduling and advisory periods

-

Provide flexibility for local leaders to adopt new approaches to staffing that favor personalization across boundaries of grade levels, departments, and other traditional organizing features that can fragment schools

This may also include providing guidance on school designs that minimize student transitions between pre-k, elementary, middle, and high school and between classes in ways that support the development of consistent, stable relationships. Such designs may include longer grade spans that reduce the number of school-to-school transitions, looping, and preschool transition plans.

-

Providing training, time, support, and funding for consistent communication between school and home. States can provide—or support districts and schools in providing—guidance and professional development for effectively and flexibly conducting conferences with students, teachers, and families and caregivers. For example, when outreach is scheduled around families’ and caregivers’ availability, they are more likely to become involved in school activities. This may happen through regular check-ins with culturally and linguistically responsive communication via positive phone calls, emails, and text messages. State agencies can also provide translation services and provide templates in various languages for commonly used documents.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of supporting relationship-centered learning environments.

Resources

- Developing State and District Parent Engagement Policies (National Association of State Boards of Education, Brief)

- How the Science of Learning and Development Can Transform Education (Science of Learning and Development Alliance, Brief)

- Reunite, Renew, and Thrive: Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Roadmap for Reopening School (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, Guide)

Policy Strategy 2 Foster Safe and Inclusive Learning Environments

In addition to creating consistent, caring learning environments, it takes a set of proactive efforts to ensure that these environments are inclusive and culturally affirming for all students. Transforming learning environments so that every child feels safe and welcome requires establishing identity-safe, culturally affirming environments; trauma-informed and healing-oriented supports; and measures of school climate to guide improvement efforts.

Educators can foster inclusion by directly addressing stereotype threats and creating identity-safe, culturally affirming learning environments. Both inside and outside of school, students often receive messages that they are less valued or less capable as a function of their race, ethnicity, family income, language background, immigration status, dis/ability status, gender, sexual orientation, or other status. When those views are reinforced and internalized, they can become self-fulfilling prophecies. Stereotype threat, “a type of social identity threat that occurs when one fears being judged in terms of a group-based stereotype,” has been found to induce the body’s stress response, leading to impaired performance on school tasks and tests that does not reflect students’ actual capacities.

When adults appreciate and understand students’ individual experiences, assets, needs, and backgrounds, they can support students in ways that counteract societal stereotypes that may undermine students’ confidence. Such knowledge of students and respect for their backgrounds and their societal stressors can help teachers design instruction in ways that build their confidence and interrupt the negative effects of discrimination.

Identity-safe learning environments, in which all students feel seen and valued, promote student achievement and attachment to schools. These kinds of learning experiences enable students to feel a strong sense of safety, belonging, and purpose, which in turn increases their ability to learn and engage with instructional content. Research has found that children are better able to learn and take risks when they feel both physically safe, with consistent routines and order, and emotionally and identity safe, knowing that they and their cultures are a valued part of the community. When adults have the cultural competence to respond affirmatively to negative narratives about the capabilities of students, they are better able to create an environment that enables all students to thrive.

|

Elements of Identity-Safe Classrooms Identity-safe classrooms promote student achievement and attachments to school. The elements of such classrooms include:

Source: Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. Drawing on Steele, D. M., & Cohn-Vargas, B. (2013). Identity Safe Classrooms: Places to Belong and Learn. Corwin Press. |

If students are to feel safe and valued, they must be understood and respected by educators as well as other adults in their learning communities. Educators play a critical role in student learning through their perceptions about their students and feedback they provide. However, evidence suggests that educators often inaccurately characterize student ability and behavior based on race and ethnicity or other characteristics. When educators perceive students as less capable based on their identities, this can affect their ability to perform academically. Educators and other adults must have opportunities to develop the skills and awareness necessary to create and maintain inclusive learning communities in which students are not subjected to social-identity or stereotype threats or misperceptions about their abilities and behaviors. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information on creating identity-safe classrooms and culturally responsive pedagogy.)

More than two thirds of U.S. children under the age of 16 experience at least one traumatic event, including abuse or neglect, hunger, homelessness, witnessing domestic violence, the sudden death of a loved one, or community or school violence. Trauma and adversity can lead to chronic stress, which damages the chemical and physical structures of a child’s developing brain and can lead to problems with attention, concentration, memory, and creativity. Children experiencing trauma are also more likely to be easily distracted, have trouble calming themselves, and become disengaged from school. Exposure to trauma as a child can also lead to negative long-term physical and mental health outcomes.

Becoming a trauma-informed and healing-oriented school involves providing administrators, educators, and other school personnel with the knowledge and preparation to recognize and respond to those impacted by traumatic stress within the school community and to promote wellness for all students. (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information.)

Although understanding the impact of trauma on learning is critical for practitioners, a focus on trauma alone may be incomplete. For example, understandings of trauma-informed practice can focus attention on the individual experience, obscuring the fact that collective trauma can be held in marginalized communities. Attention to individual trauma can also provide little insight or urgency into addressing root causes of trauma in communities that are disproportionately affected by negative economic, racial, and environmental conditions. Finally, a focus on trauma alone runs the risk of focusing on trauma intervention and treatment rather than fostering the overall well-being of the individual who has experienced adversity and harm.

Trauma- and healing-informed schools implement practices that promote wellness for all students, in addition to targeted supports for students dealing with trauma and other challenges, as part of their school support systems. (See Policy Strategy 4: Establish Integrated Support Systems for more information.)

A positive school climate supports students’ growth across all domains of development while reducing the stress and anxiety that create biological impediments to learning. Such an environment takes a whole child approach to education, seeking to address the distinctive strengths, needs, and interests of students as they engage in learning. For example, a review of school climate studies found that a positive school climate can reduce the negative effects of poverty on academic achievement. Researchers found that the most important components of school climate that contributed to student achievement were associated with relationships between students and teachers, including aspects such as warmth, acceptance, and teacher support.

To create and maintain environments filled with safety and belonging, it is important to understand how students, educators, and families and caregivers experience the school environment. One way to accomplish this is through school climate surveys, which can signal that school climate is a priority, highlight important school practices that are often overlooked or are experienced differently by some students, and identify areas of growth and progress. The National School Climate Center outlines 14 dimensions that cover all aspects of the school environment, ranging from physical and emotional safety and the physical maintenance of the school building and grounds to relationships, engagement, and a sense of belonging.

Research has shown that the condition of a school building significantly impacts students’ physical and mental health and educational achievement. However, many of the nation’s approximately 90,000 public school buildings not only are detrimental to student learning but also are bad for students’ physical and mental health. A 2014 study from the National Center for Education Statistics found that the average age of a public school building was 44 years. This study also found that nearly one quarter of public school buildings were in either poor or fair condition. These building issues disproportionately impact schools in low-wealth communities. A study that looked at school facility funding between 1995 and 2004 found that school districts in high-wealth communities spent 178% more per pupil on facilities than districts in very low-wealth communities.

The marked difference in education spending between high- and low-wealth communities has to do with the source of capital funding. A 2021 study found that the federal government provides only 1% of funding for school facilities and that, on average, states supply 22% of the funding. On average, local school districts are responsible for 77% of the financing of school facilities. However, between fiscal years 2009 and 2019, 11 states (Idaho, Indiana, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wisconsin) provided no state funds for public school facilities. Local funding for school facilities comes almost exclusively from property tax levies.

Modern educational facilities and materials are prerequisites to ensure students and teachers can engage in meaningful learning. Facility quality has been linked to the health of students and school-based personnel, student achievement, teacher performance, and educator satisfaction. Specifically, exposures to mold, poor ventilation, uncomfortable temperatures, inadequate lighting, overcrowding, and excessive noise can negatively impact the health of children and adults in schools. In contrast, new, rebuilt, or renovated schools can positively influence student test scores, student attendance, and teacher performance. Educational facilities thus clearly play a major role in creating safe, healthy, and comfortable learning environments for students and school staff.

Students are also at risk of exposure to lead in school drinking water, which research shows can cause serious irreversible health issues for children, even at very low levels. A 2017 Government Accountability Office (GAO) nationally generalized survey found that just 43% of school districts, serving 35 million students, tested their drinking water, and 37% of these districts found elevated levels of lead. The Environmental Protection Agency provides guidance and resources on testing and eliminating lead in school drinking water; yet no federal law requires schools to test their drinking water for lead, and only 12 states and the District of Columbia require it for their schools.

It is difficult to put an exact number on how much it would cost to bring all our public schools up to good working condition, but multiple estimates suggest the cost is upward of $200 billion. A 2020 GAO study found that 54% of “public school districts need to update or replace multiple building systems or features in their schools.” The U.S. Department of Education estimated in 2014 that the cost of bringing all public school facilities into good condition was approximately $197 billion. Adjusted for inflation, the cost would come to $220 billion in today’s dollars. Another national study estimates that annual spending on public school facilities needs to increase by $46 billion, or about $900 per student, to meet current needs. Without additional federal or state funding, it will not be possible for our public schools, especially those in low-wealth communities, to meet this funding need.

Policy Actions

States can support districts and schools in creating safe and inclusive environments by:

-

Promoting the use of evidence-based, data-driven approaches to improve school climate and foster strong relationships, community, and well-being. Such approaches include adopting school climate surveys to evaluate how students, educators, and families and caregivers experience the school environment and then including that school climate survey data in state accountability plans for improvement purposes. States can also conduct assets and needs assessments to identify appropriate supports (e.g., counselors, social workers, school psychologists, social-emotional programs, trauma-informed practices) for districts and schools as well as the barriers they face in responding to the unique needs of students, educators, and families and caregivers.

-

Providing educators with training and professional development opportunities on how to create safe and inclusive learning environments for all students. Learning opportunities for educators may focus on:

-

Cultivating communities of belonging in schools and classrooms

-

Delivering culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy

-

Implementing identity-safe school and classroom guidance

-

Using climate survey data to improve teaching and learning, including how to analyze data by race, gender, disability, native language, and other status to identify opportunities to understand trends and respond to how different student groups may be differently experiencing elements of school climate

-

Dedicating funding, developing and enforcing standards, and reducing disparities between high-wealth and low-wealth communities to build, renovate, and maintain educational facilities and classrooms that are conducive to learning. States' standards should ensure that every student learns in physically and environmentally safe classrooms and in healthy and sanitary conditions. For example, lighting, temperature, acoustics, air quality, space, and environmental factors may be considered. States may need to update heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems; repair leaky roofs; fix broken windows; reduce excessive noise; remove mold or other allergens; build additional instructional spaces; and employ trained staff to ensure regular building inspections and maintenance. States can also set strict water quality standards for schools, require the ongoing testing of school drinking water, and invest in water filters and other measures to eliminate contaminants in school drinking water. States may also maintain the quality of educational infrastructure through codes, policies, and regulations that specify the roles and responsibilities of states, districts, and schools.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of creating inclusive environments.

Resources

- Gauging School Climate (National Association of State Boards of Education, Journal)

- Measuring School Climate and Social and Emotional Learning and Development: A Navigation Guide for States and Districts (EducationCounsel; Council of Chief State School Officers, Guide)

- School and Classroom Climate Measures: Considerations for Use by State and Local Education Leaders (RAND Corporation, Report)

Policy Strategy 3 Adopt Restorative Approaches to Discipline

Many states and school districts have adopted zero-tolerance policies, an approach that allows a student to be temporarily or permanently removed from school for a number of discipline issues, from serious, violent behavior to minor dress code infractions. Zero-tolerance policies have led to high rates of suspension and expulsion, which have disproportionately excluded students of color and students with disabilities from schools. Evidence shows that this is due largely not to worse behavior by these student groups but to harsher treatments for minor offenses, such as tardiness, talking in class, and other nonviolent behavior.

Disproportionalities in suspension and expulsion rates between students of color and their white peers appear as early as preschool and continue throughout k–12. These punitive, exclusionary punishments are particularly inflicted on Black youth, who often receive harsher punishments for minor offenses and are more than twice as likely as white students to receive a referral to law enforcement or be subject to a school-related arrest. Research shows that exclusionary practices, such as suspensions and expulsions, are ineffective at improving outcomes for students and improving school climate and promote disengaged behaviors, such as truancy, chronic absenteeism, and antisocial behavior, which exacerbate a widening achievement gap.

Disproportionalities in suspension and expulsion rates between students of color and their white peers appear as early as preschool and continue throughout k–12. These punitive, exclusionary punishments are particularly inflicted on Black youth, who often receive harsher punishments for minor offenses and are more than twice as likely as white students to receive a referral to law enforcement or be subject to a school-related arrest. Research shows that exclusionary practices, such as suspensions and expulsions, are ineffective at improving outcomes for students and improving school climate and promote disengaged behaviors, such as truancy, chronic absenteeism, and antisocial behavior, which exacerbate a widening achievement gap.

Students with disabilities are also more likely to face harsh disciplinary practices. According to the 2017–18 Civil Rights Data Collection, 80% of students who were subjected to physical restraint were students with disabilities. Additionally, 77% of students who were subjected to seclusion were students with disabilities. These practices are often overused or misused and can lead to physical injuries and psychological trauma for students and teachers and, therefore, should be replaced with less harmful, inclusionary practices.

Unfortunately, resource inequities have led to many students being more likely to attend a school with police officers but no school counselors or mental health professionals. This is despite research that indicates that a punitive environment undermines learning by increasing anxiety and stress, which drains energy available to address classroom tasks; by limiting students’ abilities to meaningfully engage with peers and adults; and by degrading the sense of community in a school.

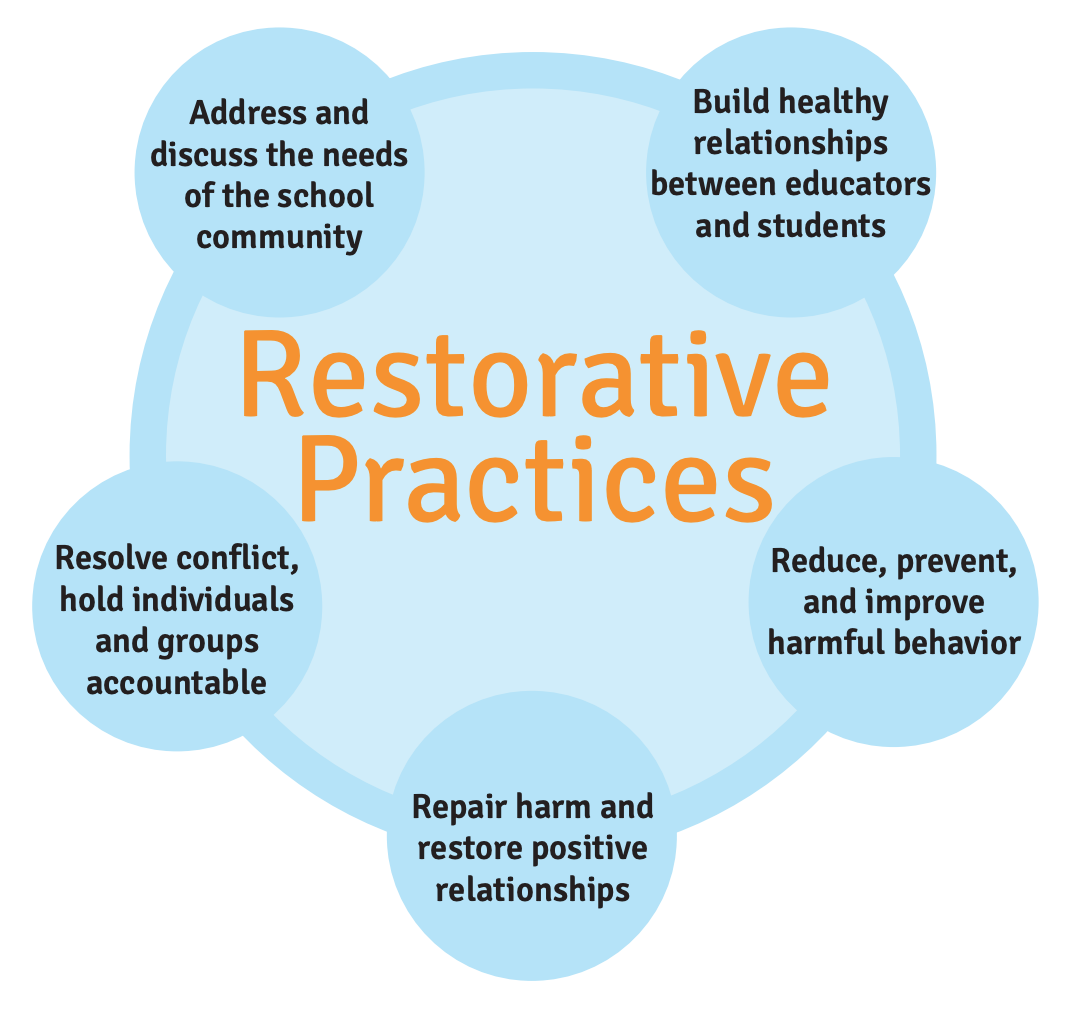

To mitigate these effects, exclusionary practices should be replaced with evidence-based restorative approaches that recognize students’ behaviors as a demonstration of developmental need or trauma and that provide tools for educators and students to proactively cope with behavioral issues. (See Figure 2.2.) Restorative approaches are “processes that proactively build healthy relationships and a sense of community to prevent and address conflict and wrongdoing.” Restorative practices are implemented in classrooms through universal interventions, such as daily class meetings, community building circles, and conflict resolution strategies, which are also part of many social and emotional learning programs.

A restorative approach deals with conflict by identifying or naming the wrongdoing, repairing the harm, and restoring relationships. As a result, this approach is built on strong relationships and relational trust, with systems for students to reflect on mistakes, repair damage to the community, and get counseling when needed. Creating an environment in which students learn to be responsible and are given the opportunity for agency and contribution can transform social, emotional, and academic behaviors and outcomes.

Source: Schott Foundation, Advancement Project, American Federation of Teachers, & National Education Association. (2014). Restorative practices: Fostering healthy relationships and promoting positive discipline in schools.

Such approaches include culturally responsive social and emotional learning (SEL) programs, which help students build competencies and skills to proactively handle conflict and frustration, and educative and restorative practices, which support the creation of responsive learning environments. These restorative approaches are centered on strong relationships and focus on skills such as self-reflection, communication, community-building, and making amends. It is important to note, however, that SEL programming must be culturally affirming, not another form of policing black and brown students. This often happens when SEL is used as a mechanism for schools to regulate student behavior to conform to cultural and gender norms and values instead of encouraging students to exercise agency and interrogate systems of oppression.

Policy Actions

States can adopt and invest in inclusive, restorative, and educative approaches to school discipline practice and policy by:

-

Replacing zero-tolerance policies and the use of suspensions and expulsions for low-level offenses with evidence-based restorative approaches that make schools safer for all students. Exclusionary policies, including in- and out-of-school suspensions, expulsions, and restraint and seclusion practices, may start in early childhood and continue through secondary school. States can reduce the use of these exclusionary policies and practices by, for example, limiting or banning zero-tolerance policies, particularly for young children; requiring schools to consider multiple factors before suspending or expelling a student, including age, discipline history, disability status, seriousness of the violation, and whether other interventions or restorative practices should be used; and including suspension and expulsion rates as an indicator in school accountability and improvement systems. States can also provide guidance and funding for implementing evidence-based approaches that support young people in learning key skills and developing responsibility for themselves and their communities (e.g., SEL programs, restorative practices). States can also provide guidance and support to schools and districts to eliminate discriminatory dress code policies, “willful defiance,” and other minor infractions that discriminate against marginalized student groups.

-

Investing in critical mental and behavioral health services. States can invest funding into mental health services, social-emotional supports, staff preparation and training in restorative justice practices, and needed social services (e.g., counselors, social workers, school psychologists, mentors) and can provide guidance to schools and districts to do the same.

-

Providing training on restorative practices for all school staff and others dealing with youth to reduce disciplinary disparities. In addition to school staff, training should be provided to school resource officers (SROs), after-school and out-of-school program staff, and others working directly with young people. Such trainings may include approaches that help staff work with students by focusing on their strengths and individual capacities and connecting them with positive opportunities in the community. For schools and districts employing SROs, states can also establish standards for the appropriate use of SROs as well as criteria for hiring, training, and continuously evaluating their performance and role.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of restorative approaches to school discipline.

Resources

- Advancing School Discipline Reform (National Association of State Boards of Education, Report)

- A Restorative Approach for Equitable Education (Learning Policy Institute, Brief)

- School Discipline Consensus Report: Strategies From the Field to Keep Students Engaged in School and Out of the Juvenile Justice System (Council of State Governments Justice Center, Report)

Policy Strategy 4 Establish Integrated Support Systems

Schools must also be prepared to address the unique strengths as well as the needs of young people that may create barriers to learning and development by connecting students and their families and caregivers to services that promote holistic development. These barriers may be the result of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as physical or mental illness, abuse, neglect, food or housing insecurity, exposure to violence, divorce, loss of a parent, or other difficulties. Each year, nearly half of all U.S. children experience at least one ACE. Black and Latino/a children are disproportionately exposed to traumatic stressors. Without protective factors in place, ACEs can negatively affect children’s ability to concentrate, think creatively, and remain engaged. Ultimately, ACEs can have long-term impacts on children’s health and educational outcomes. Despite the significant numbers of students dealing with toxic and often chronic stress, schools across the nation remain dramatically understaffed with counselors and other support staff. To address these issues, schools must be supported in taking a systemwide and personalized approach to identify and address each student’s well-being and determine what additional supports are needed for the student and family.

Schools must also be prepared to address the unique strengths as well as the needs of young people that may create barriers to learning and development by connecting students and their families and caregivers to services that promote holistic development. These barriers may be the result of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as physical or mental illness, abuse, neglect, food or housing insecurity, exposure to violence, divorce, loss of a parent, or other difficulties. Each year, nearly half of all U.S. children experience at least one ACE. Black and Latino/a children are disproportionately exposed to traumatic stressors. Without protective factors in place, ACEs can negatively affect children’s ability to concentrate, think creatively, and remain engaged. Ultimately, ACEs can have long-term impacts on children’s health and educational outcomes. Despite the significant numbers of students dealing with toxic and often chronic stress, schools across the nation remain dramatically understaffed with counselors and other support staff. To address these issues, schools must be supported in taking a systemwide and personalized approach to identify and address each student’s well-being and determine what additional supports are needed for the student and family.

Several models have emerged to provide integrated student services, which link children and families and caregivers to a range of academic, health, and social services at the school site. Research has highlighted that integrated systems of support (ISS) can improve student achievement across several indicators, such as academic achievement and attendance. For example, a comprehensive review of ISS models found that these models offer a promising approach to support student achievement and highlighted common components of these approaches. These include needs assessments, coordination of supports, integration of supports within schools, community partnerships, and data tracking.

|

Meeting Students’ Mental Health Needs

Research shows that good mental health is key to the success of children and adolescents in school and life. According to the National Association of School Psychologists, mental health is not simply the absence of mental illness but also the promotion of overall wellness; social, emotional, and behavioral health; and the ability to cope with life’s challenges. Left unaddressed, mental health problems can lead to costly negative outcomes, including academic and behavioral issues, disengaging and dropping out, and delinquency.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2013 that roughly 1 in 5 children and adolescents experience a mental health problem during their school years, and the prevalence of these conditions in young people was increasing. Examples include stress, anxiety, bullying, family problems, depression, and alcohol and substance abuse. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues and the need for providing children and youth necessary social and emotional supports. Unfortunately, many young people, particularly students from low-income families and students of color, do not have access to the help they need, and schools and communities often have insufficient means to provide mental health services.

In spring 2021, the Education Commission of the States released a line of resources to help policymakers understand the state of mental health policy for children and adolescents and to provide the resources schools and communities needed to support positive student mental health. These resources are as follows:

|

Examples of integrated support systems include comprehensive, multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) and community school initiatives. Early warning indicator systems can also be adopted to help schools identify students who are falling off track academically and may need additional supports.

In recent years, schools have tried to create integrated support systems by building multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS). MTSS typically include tiers of support that promote learning and development in ways that prevent difficulties and that provide supplemental supports and intensive intervention when needed. These tiered models begin with universal designs for learning and personalized teaching and provide more intensive academic and nonacademic supports to ensure that all students can receive the right kind of assistance without stigma or delays. It is important that interventions, not students, are tiered; that supports are implemented with fidelity; and that providers take an asset-based approach to building upon student strengths instead of focusing just on deficits. The key is to take a whole child approach in which students are treated in connected, rather than fragmented, ways and in which care is personalized to the needs of individuals.

The integration of education and health, mental health, and social welfare supports can also be accomplished through a community school approach. Community school initiatives are driven by partnerships between community organizations, nonprofits, and local government agencies to provide resources for youth and adults. Community schools have four key pillars—(1) integrated student supports, (2) expanded and enriched learning time and opportunities, (3) active family and community engagement, and (4) collaborative leadership and practices—to support this integration of services. (See Figure 2.3.) These schools often draw from a wide range of community and cultural resources, including partnerships with families, to strengthen trust and build resilience as children have more support systems and as people work collaboratively to help address the stresses of poverty and the associated adversities children may face.

Source: Partnership for the Future of Learning. (2018). Community schools playbook.

While community schools vary in their approaches and structures, evidence shows that they can improve outcomes for students, including attendance, academic achievement, high school graduation rates, and reduced racial and economic achievement gaps. A recent RAND study of New York City’s large-scale community schools initiative shows that community schools can work at scale. Promising results include a drop in chronic absenteeism, with the biggest effects on the most vulnerable students, and a decline in disciplinary incidents. Students were more likely to progress from grade to grade on time, accumulate more course credits, and graduate from high school at higher rates. (See Investing Resources Equitably and Efficiently for more information on investing in integrated student supports and community schools.)

Strong school–community partnerships can play a critical role in efforts to support the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children and youth. Engaging community partners allows schools to forge a common vision for student success across settings and reinforces the understanding that learning and development happens outside of the traditional school day. School–community partnerships can also be instrumental in establishing two-way communication and trust between schools and community organizations and in ensuring young people are surrounded by consistent, caring relationships.

Research shows that key indicators, including chronic absenteeism, course performance, and credit attainment, can help predict students at risk for dropping out as early as middle school. School-to-school transitions (e.g., between pre-k and kindergarten, elementary and middle school, or middle and high school) and the change in routines, environments, and relationships have been identified as key points of disengagement for students. Early warning indicator data systems, particularly when used at these transition points, can help educators monitor students who are falling off track. Most importantly, students identified through early warning indicator systems can be connected to comprehensive school interventions, including tutoring and academic integrated student supports, mentoring programs, and social and emotional learning supports.

Policy Actions

States can invest in integrated systems of support to better serve the holistic needs of students and families and caregivers by:

-

Identifying existing assets (including out-of-school resources and factors) and barriers to learning and the appropriate supports needed to enable positive youth outcomes. Successful implementation of integrated student supports (ISS) starts with an inclusive and collaborative process for engaging students and families in identifying needs and assets and then using this information to develop appropriate partnerships. To facilitate this process, states can develop districtwide and schoolwide assets and needs assessments and support districts and schools in using them. To be most impactful, the assets and needs assessment should examine existing partnerships and the resources available to address potential service gaps (e.g., counselors, social workers, school psychologists, social-emotional curricula, trauma-informed practices). States can provide districts with guidance, technical assistance, resources, and tools to help them ensure that the ISS selected are tailored to meet the needs of students, families, and communities. Districts can provide schools with an analysis of school-level data and training on how to use that data to support continuous improvement in providing these important services to students and families.

-

Adopting and supporting evidence-based integrated student support frameworks. This may include establishing or adopting statewide research-based ISS protocols or frameworks and developing and coordinating policies that connect multiple initiatives, such as multi-tiered systems of support models, to guide implementation in schools and districts and support improved practice at scale. States can also adopt legislation and provide funding for ISS models.

-

Investing in and supporting evidence-based community school initiatives. This may include adopting legislation and providing funding for community school models and issuing a state board resolution in support of community schools to encourage district uptake of a community school strategy and help direct funding to support implementation. Community school funding can include support for coordinators—dedicated, full-time staff members in each school or district who understand the community. Coordinators can help manage partnerships, engage students and families, and support collaborative governance structures.

-

Supporting coordination at multiple levels—from the district to the school building. States can establish a coordinating infrastructure within communities (from community schools to provider networks to children’s cabinets). This would support collaboration at scale by creating aligned systems and structures for provider and school connection. States can also leverage similar or complementary efforts on data sharing, training, goal setting, and communications to improve connections across systems. (See Investing Resources Equitably and Efficiently for more information on investments in community schools.)

-

Supporting schools and districts in developing and using early warning indicator systems to provide targeted student supports. These early warning systems should use easily accessible data—attendance, behavior, class performance—to identify and provide integrated supports to students who struggle with school-to-school transitions (e.g., between elementary and middle school and between middle and high school) or who are falling off track academically.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of integrated support systems.

Resources

- Building Systems of Integrated Student Support: A Policy Brief for Local and State Leaders (America’s Promise Alliance; Center for Thriving Children, Brief)

- Community Schools Playbook (Partnership for the Future of Learning, Playbook)

- Integrating Social and Emotional Learning Within a Multi-Tiered System of Supports to Advance Equity: SEL MTSS Toolkit for State and District Leaders (Council of Chief State School Officers; Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning; American Institutes for Research , Toolkit)

Policy Strategy 5 Provide High-Quality Expanded Learning Time

High-quality expanded learning time (ELT) should be readily available and easily accessible to help address students’ academic and nonacademic needs. Large disparities exist in the amount of exposure to learning opportunities between students from low-income families and students from affluent families, including before and after school and during school breaks. For example, research has found that students from middle- and upper-income families typically spend 6,000 more hours in educational activities than students from low-income families by the time they reach the 6th grade. Another study found that the cumulative summer learning gap over multiple years accounts for more than half of the 9th-grade achievement difference between students from low-income families and their more affluent peers. This difference in 9th-grade achievement contributes to the likelihood of high school students entering college-track programs and meeting college-going requirements. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these inequities and prompted many states, districts, and schools to provide high-quality ELT.

Expanded learning time opportunities can include high-quality tutoring; after-school and summer learning programs; and early learning programs.

Rather than engaging in tracking, which differentiates students’ access to quality curricula and has been found to depress the achievement of low-tracked groups, providing access to high-quality tutoring opportunities is an effective means for schools to provide supplemental supports. There is well-established literature on the positive effects of tutoring, which can produce large academic gains. Effective tutoring is accomplished by a focused group of trained individuals working consistently with individuals or small groups of students. In particular, research supports high-dosage tutoring, in which tutors work consistently at least 3 days per week for full class sessions (during or after school) with students one-on-one or in very small groups, often accomplishing large gains in relatively short periods of time.

These tutors may be specially trained teachers who work in programs with a set of well-defined methods and who work with students one-on-one or in small groups. Reading Recovery, one example of this type of program, has been found to have strong positive effects on reading gains for struggling readers, including English learners and students with special education needs. The tutors may also be recent college graduates, including AmeriCorps volunteers, who receive training to work with students, as in the Boston MATCH Education program. In daily 50-minute sessions added to their regular math classes, two students working with a tutor gained an additional 1 to 2 years of math proficiency by focusing on the specific areas they need to master while also preparing for their standard classes. Tutors in programs such as these have the advantage of well-developed curriculum with frequent formative assessments to gauge and guide where support is needed.

After-school and summer programs are another way to enable access to important supplemental supports during out-of-school time. After-school programs are a common way ELT is incorporated into a school’s system of supports. These opportunities can accelerate learning and reduce opportunity gaps between what students from low-income families and their peers from middle- and upper-income families experience during out-of-school hours. Yet additional time will not in and of itself promote positive student outcomes. Quality out-of-school programs that produce positive effects on outcomes offer targeted instruction focused on particular academic and/or social-emotional skills; create a warm, positive climate; enable consistent and frequent participation; and employ a stable group of trained, dedicated instructors. When out-of-school time programs reinforce a school’s curriculum, pedagogy, and core values, they are more effective in supporting student outcomes, growth, and engagement. ELT includes summer learning programs, which have been found to be most effective when they offer nonacademic enrichment along with academic supports, use a trained group of stable staff, are experienced by students for multiple summers, and provide purposeful curriculum.

High-quality preschool is another form of ELT that yields substantial gains, especially when students have access to full-day programs. For example, research shows that increased daily learning time can yield bigger benefits for preschool-age children as well. Yet many children do not have access to early learning programs due to inadequate public funding and because many run only 3–4 hours each day, making them inaccessible to working families. While some part-day programs have shown strong results, most of the highly effective programs, especially for children from low-income families, provide full-day preschool. An evaluation of the long-term impact of the Chicago Child–Parent Centers, for example, showed that children attending the program for a full day scored better on measures of social-emotional development, math and reading skills, and physical health than similar children attending the same program for only part of a day. A national evaluation of Head Start also suggests that children who enrolled in the full-day program performed better in reading and math.

Policy Actions

States can provide high-quality ELT to close opportunity and enrichment gaps by:

-

Funding and supporting high-quality expanded learning programs. This may include investments to expand before- and after-school programs that provide enriched learning, work-based and civic engagement opportunities, summer learning programs, and tutoring (e.g., Reading Recovery, National Center on Intensive Intervention, What Works Clearinghouse). This may include establishing appropriately funded partnerships with community organizations, public agencies, and the business sector. These partnerships can provide support—with mentoring, enrichment, whole child wellness, and academic progress via additional staffing and program augmentation that nurtures positive relationships—and expand access to community-based and career and technical learning experiences.

-

Expanding the reach, duration, and quality of early learning programs. States can do the following:

-

Define and use state quality standards that incorporate evaluations of adult–children interactions, adult–child ratios, and facility requirements

-

Develop quality rating and improvement systems to support continuous improvement, reinforce quality standards, and provide a basis for program accountability

-

Link funding to ratings to promote quality

-

Invest in strengthening teacher quality by providing accessible, specialized training, coaching, and incentives (See Building Adult Capacity and Expertise for more information on training, recruiting, and retaining educators.)

-

Coordinate administration of early learning programs through a state children’s cabinet and by instituting cross-agency data-sharing agreements (See Setting a Whole Child Vision for more information on coordinating and streamlining services.)

-

Strategically blend and braid multiple funding sources to increase access and quality (See Investing Resources Equitably and Efficiently for more information on investing in high-quality child care and preschool programs.)

-

Establishing statewide standards for the quality of expanded learning programs. States can work with expanded learning experts, such as statewide after-school networks, to set standards to be used to review, control the quality of, and improve expanded learning programs. States can also support districts and communities in applying the key research-based principles of effective ELT, including providing active and engaged learning experiences, engaging families, ensuring a well-prepared and diverse staff and investing in professional development, setting explicit goals and aligning programming with those goals, and promoting students’ health and wellness.

-

Facilitating necessary communication and collaboration between in-school and out-of-school partners. This may include removing barriers to sharing facilities between schools and community-based organizations to mitigate the out-of-school time opportunity gaps; finding opportunities for appropriate data sharing; supporting joint training and professional development; and including and sharing information on the availability of programs with a broad range of stakeholders to ensure teachers, families, caregivers, and others dealing with youth know the range of enrichment and well-rounded educational opportunities available for students.

View the State Policy Library for additional examples of expanded learning opportunities.

Resources

- 2021 Summer Learning and Enrichment: State Guidance for District and School Leaders (Council of Chief State School Officers; National Governors Association, Guide)

- Community Learning Hubs (Afterschool Alliance, Guide)

- Time in Pursuit of Education Equity: Promoting Learning Time Reforms That Cross Ideological Divides to Benefit Students Most in Need (AASA, Article)